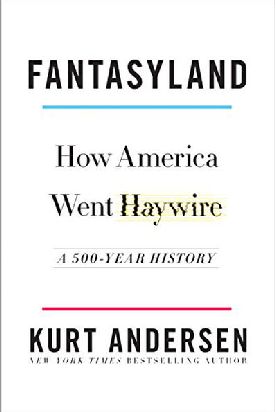

Fantasia on a Theme

From The Weekly StandardKurt Andersen may be right in supposing that what looks like Americans’ increasing inability to distinguish fantasy from reality is the big topic of our times, and there are at least 2 or 3 of his 46 chapters in Fantasyland in which he does justice to his subject. His rapid tour d’horizon on New Age spirituality, homeopathic medicine, pseudoscience and the paranormal, the psychiatric vogue for “recovered memory syndrome,” and the legal craze in the 1980s and early ’90s for prosecutions of imaginary, “Satanist”-inspired child abuse is a valuable compendium, particularly for young people who didn’t live through the period when such things were taken seriously. Above all, we should be glad of his documentation of how those false-belief fads — and other species of hokum, such as the anti-vaccine hysteria of the early 2000s — were treated with seriousness by the media about whose traditional role as gatekeepers to “reality” he is otherwise so solicitous.

Andersen is also sound on some other sorts of crazy and socially harmful fantasies that are still very much with us, such as conspiracy theories, pornography, the infantilization of pop culture, celebrity culture, reality TV, violent video games, legalized gambling, and the boom in plastic surgery. Yet he casts his net so wide that, along with these things, he pulls up Civil War reenactors and war-gamers who are a different kind of thing altogether. Imaginative re-creation of a known reality for the sake of knowing it better is surely something to be distinguished from the fanciful invention of non-realities that are then treated as real. You could even argue that cosmetic surgery is not qualitatively different from cosmetics, which have been around (along with condemnations of them) forever.

It would be an interesting argument to have, anyway. But Andersen—a novelist and the host of the public-radio show Studio 360 — is not much interested in the hard work of argument, since he is not really writing for anyone who doesn’t already agree with him. He is obviously not interested in selling his thesis, for example, to the “huge national audience” to which, as he asserts without bothering to demonstrate, Rush Limbaugh daily brings “a sociopolitical alternate reality.” It is one thing to say that you disagree with somebody, but Andersen’s way of saying he disagrees with you, like that of so many other polemicists nowadays, is to tell you that you are living in an “alternate reality.” No evidence, argument, or persuasion is required.In the book’s subtitle, which is How America Went Haywire: A 500-Year History, the word “America” does not really denote the country lying between Canada and Mexico. Nor is “America” the country of which Kurt Andersen himself is a citizen. No, the country that allegedly started going “haywire” 500 years ago, even before it was a country, is itself a fantasyland, a simulacrum of the real America but comprising only an admittedly large population of suckers and the marginally cleverer con men and women who have preyed on them for centuries and are still preying on them. Andersen may describe himself as an American, but he writes about America as if he and the class of enlightened sophisticates to which he belongs stand outside it, laughing at the monkeyshines of those credulous Americans he purports to describe.

It is a familiar posture, pioneered a century ago by H.L. Mencken and since adopted by the academic left with such unanimity as to be almost a requirement for admission to the number of those who belong, or aspire to belong, to our ruling elites—as they occasionally let slip when, like Peter Jennings in 1994, they describe the electorate as being a 2-year-old having a temper tantrum or, like Barack Obama in 2008, as clinging “to guns or religion or antipathy toward people who aren’t like them.” Hillary Clinton may have apologized for saying “half of Trump supporters” could be put in a “basket of deplorables,” but no one can have doubted that it was what she really thought of them. It’s what the whole class to which she belongs thinks of them, as their support for Trump, if nothing else, shows they very well know.

It is also the class to which Andersen belongs, as he acknowledges when he quotes Obama on the bitter clingers and comments: “Sure, it was condescending, but it was also true.” His book amounts to little more than an elite attempt to justify its author’s perception of the America for which he harbors such contempt. Remarkably, for a book that’s all about the blurred lines between reality and fantasy, it never troubles to define what “reality” is. Why? Apparently because it never occurred to Andersen to doubt his readers will be as sure as he is that they already know what reality is and that it must be coterminous with the progressive narrative of the last 50 years, culminating in the enthronement of that ultimate fantasist, Donald Trump.

The delightful discovery with which Andersen hopes to entertain readers is that the predominantly right-wing (as he sees it) and American addiction to the merely fantastical actually goes back 10 times as far—in fact to the very beginnings of the European settlement of the continent. In effect, he has started with Trump and worked backward—until he suddenly found that it’s been Trump and Trumpism (or as good as) all along. His start date of 1517 appears to have been chosen in honor of Martin Luther’s launching the Protestant Reformation in that year. To Andersen, “the disagreements dividing Protestants from Catholics were about the internal consistency of the magical rules within their common fantasy scheme.”

In his view, Luther’s real revolution was the invention of a kind of “DIY Christianity” that a century later issued in the “nutty religious cult” that settled Massachusetts and so paved the way for such natural successors three or four centuries later as Billy Sunday, Billy Graham, Pat Robertson, the Pentecostal movement, Jim Jones of the People’s Temple and cyanide-laced Kool- Aid fame, and, of course, Donald Trump. The rhetorical temptation must have been very great here, but even Mencken might have balked at the historical obtuseness of finding no important difference between 17th-century English Puritans in Massachusetts and such latter-day successors as these. On more than one occasion Andersen even implies that Americans and their forebears are comparable to Islamist terrorists.

To a man with a hammer, they say, everything looks like a nail, and Andersen’s hammer is fantasy, whether of God or of gold, of show-business or suburbia. Writing history backward by analyzing a contemporary phenomenon like the Disneyfication of culture (“the fantasy-industrial complex”) and then projecting it onto the past can be done only by not making elementary distinctions, especially between religion as a historical phenomenon and the fantasy-mania we are observing today, which has also affected religion.

As it has everything else, very much including Andersen’s sort of historiography, which seeks to translate historical phenomena into contemporary pop-cultural terms with which they can have had nothing to do. To him there are no difficulties, no mysteries in the past, just stuff that we’ve all seen already on TV and that the superior among us have always laughed at. Thus, Joseph Smith’s Mormonism—and perhaps Christianity itself—is described as biblical “fan fiction.” “We’ll give Jehovah a son,” he writes of the authors of the New Testament, “part god and part human!” Yeah, that must be how it happened: just like a Hollywood superhero pitch session. Elsewhere, trying to be witty, he writes of the biblical account of Jesus’ 40 days in the wilderness as the time when “Satan tried to make Jesus prove he had superpowers and come to the dark side.”

Talk about fantasy! Talk about (as he also does) anti-intellectualism! Yet Andersen has no fear of not being taken seriously by an audience that presumably eats such stuff up. Likewise, he has no fear of contradiction in gratuitously treating as fantasies things like “gun rights hysteria,” “free-market fundamentalism,” or the ideas (unspecified) of the “hysterical true believers” who made up the Tea Party—things that are fantastical only by virtue of belonging to the politically disfavored. Andersen apparently thinks that climate change “denialism” is equally the fantasy of those who regard it as a “hoax” and those who merely dissent from the economically ruinous left-wing consensus as to what to do about it.

Andersen leaves out certain fantasies of the left that might prove inconvenient to his thesis. He has much to say, for instance, about right-wing “McCarthyism” back in the 1950s, but next to nothing about the biggest fantasy of the 20th century, that of Marxist communism, which, though not American in origin, once enjoyed a considerable vogue in this country, especially among the privileged classes, and is now enjoying a resurgence among the academic left. Andersen is all over cosmetic surgery but has not a word to say about the much more drastic (and arguably much more fantastical) idea of sex-reassignment surgery that has lately become all the rage among progressives and in the media.

In the fantasyland environment of today, it is ill-advised to make fantasy a partisan subject, the property of one political party almost to the exclusion of the other. If Andersen is right in thinking that it is primarily Republicans who have gone off the deep end for fantasy, then he cannot also be right in thinking that it is the salient feature of our whole culture today, including our political culture, let alone something that has been present in American culture since the beginning. He ends up suggesting that only the things (or political parties) he likes are immune to the fantasy bug—or, when you get right down to it, that only he himself is. In other words, he might as well be calling himself, as Rush Limbaugh does himself, the “mayor of Real-ville.”

Andersen periodically makes little self-deprecatory gestures, such as admitting that he once played a video game often enough to get good at it and that, in writing about what he sees as the middle-class fantasy of the SUV and the pickup (it goes with the Frank Lloyd Wright fantasy of the suburbs), he owns a Land Rover. But the only fleeting moment of real self-awareness comes a few pages from the end of the book, where he writes: “Mix the Protestant impulse to find the magical meaning and purpose in everything with the Enlightenment’s empiricism, and you get our American mania for connecting all the dots, irrationality in rationalist drag”—and then he footnotes the bit about “connecting all the dots” thus: “I realize: given this book, I’m one to talk.”

And yet this momentary flash of insight doesn’t translate into any overall awareness that he himself and the book he has written are at least as much a part of the fantasy culture he describes as those benighted religious nuts and gun nuts and free-market nuts. To claim, as Andersen does, that our country is a “fantasyland” is an obvious mistake, since in order to be able to identify it as such, you would also have to be able to identify reality as such, and that is just what we cannot do in a world in which reality has come to mean whatever we want it to mean. In other words, Andersen is just as much in thrall to his vision of reality as any of the alleged fantasists he attacks, and calling it “rationalist” no more validates his certainty than their calling theirs God-given validates theirs.

Since Andersen never gets around to it, let me attempt to define “reality.” Reality is what any two debaters or controversialists have in common—or, to put it in another way, reality is what is, if anything is, uncontroversial. Since there is very little if anything in our public discourse today that is uncontroversial, it follows that there is little or no reality anymore. Andersen does not know this, though knowing it would seem to be the minimum requirement for writing a book like Fantasyland. That makes Fantasyland itself a fantasy, though an all-too-familiar one. It is the fantasy of the intellectual that of all the rival systems competing for our attention his alone is reality-based.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.