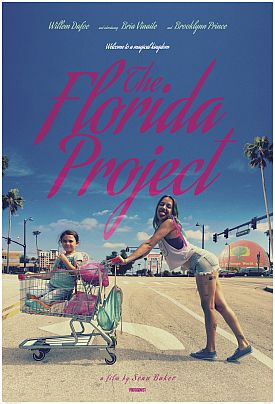

The Florida Project

The heavy-handedness of the irony in Sean Baker’s new movie, The Florida Project, begins with the opening titles, over which we hear Kool & the Gang singing “Ce-le-brate good times, come on!” while the camera introduces us to the sun-drenched exteriors of the Florida welfare-motel where the film is set and the punning “project” of the title (the Disney company’s drawing board name for Disney World in the 1950s was “The Florida Project”). It is already obvious that this is not exactly a place either for celebration or for good times. But then, from the point of view of six-year-old Moonee (Brooklynn Prince), times are good. It’s summer, and she is given free rein by her slutty, tattooed single mother, Halley (Bria Vinaite), to roam with a couple of friends through the motel’s and adjacent grounds and the strip of souvenir shops and fast food joints on the highway leading to the Magic Kingdom. “We’re just playing,” says Moonee to an adult who asks — as if to say, what else could we be doing?

There are enough conscious allusions to the great François Truffaut film Les Quatre Cent Coups (usually literally translated as The Four Hundred Blows) of 1959, particularly in the ending, that The Florida Project could be considered an unlikely homage to it, but I find the differences between the two movies more instructive than the similarities. Truffaut’s film was about what in those days was called a juvenile delinquent, 14-year-old Antoine Doinel (Jean-Pierre Léaud), who, with his mother and step-father, was barely hanging on to a barely middle-class existence. Both parents were employed, but they lived in a state of constant anxiety of slipping down the social scale and out of the ranks of the respectably independent and decent bourgeoisie — as (spoiler alert!) Antoine in fact does by the end, bringing shame on the whole family.

There is almost nothing of this social context in The Florida Project. Halley and Moonee and pretty much everybody at the Magic Castle Motel are already among the dregs of society and, outwardly at least, have no desire to be anything or live anywhere else. We catch glimpses of the life of the more socially responsible and employed classes just above them in Bobby (Willem Dafoe), the divorced resident motel manager with a mysterious but presumably rather hard-luck back story of his own, who feels compassion for his residents within the rather narrow limits set for him by the motel’s owner and the welfare authorities. But for the most part such remaining shreds and patches of the old middle class notions of decency as we see are like the strip of material with which Bobby tries to get a topless old woman (Sandy Kane) by the pool to cover up with: so pathetically inadequate to the task that there hardly seems any point to performing it.

One such remnant of old-fashioned respectability shows up when another one of the motel’s single mothers, Ashley (Mela Murder), whose little boy Scooty (Christopher Rivera) is one of Moonee’s playmates and who sometimes gives the kids free food from the back door of the waffle house where she works as a waitress, accuses Halley (accurately) of “whoring.” Halley proceeds to beat her up, thereby confirming my contention in Honor, A History that, long after the demise of the Western honor culture, the imputation of unchastity (as opposed to the reality of it) to a woman remains “fighting words” — even more so, perhaps, than the imputation of cowardice to a man. The otherwise inexplicable shame felt by so many innocent female victims of male predators, so much in the news of late, is another example of the same vestigial honor standard.

But the incident appears to have no particular significance to Mr Baker or his co-writer, Chris Bergoch, for whom it is just another example of the immaturity that elsewhere makes Halley behave more like another one of Moonee’s playmates than her mother. To their credit, they do not try to soft-pedal Halley’s manifest unfitness as a mother except insofar as it appears to be only what is expected, more or less, in the lower depths of our society which she inhabits and doubtless always will. “I’m a failure as a mother,” she says at one point with a smirk, as if to mock the whole outmoded idea that there could be such a thing. Thus the arrival on the motel’s doorstep of Child Protective Services seems inevitable from the start, and we are free to enjoy the pathos of the doomed mother-daughter relationship with a clear conscience.

Indeed, we may even pretend to ourselves that Moonee can break free of such social constraints as may be upon her, like Antoine Doinel at the end of The Four Hundred Blows — the Disney Magic Kingdom being to her what the sea was to Antoine. Of course it’s all as much a fantasy as the Magic Kingdom itself. But it is now an article of faith in our culture, and especially in Hollywood, that fantasy is not just OK but obligatory — which rather undercuts Mr Baker’s attempts to point up to us the contrast, not between existing social realities as in Truffaut’s film, but between one version of reality and the Disney fantasy just down the road from the Magic Castle Motel on Seven Dwarfs Lane, which becomes the excuse for the irony aforementioned.

Is that irony directed at the truncated family in the motel or at Disney World, of whose childish Fantasyland their lives become a parody? Pretty clearly, it is the latter, and this only makes the film’s ironies too obvious and uninteresting, as if Disney-style escapism were oblivious to the realities it is escaping from instead of using them as part of its business model in selling escape to a slightly higher class of parent than Halley. The more interesting irony would be at the expense of the validation given by the official culture, here represented by Child Protective Services, to Disney-style fantasy, their own version of which Halley and Moonee are living out in reality — to the strong disapproval of the same official culture. Pirates of the Caribbean? Great! Pirates of the Disney country’s strip malls? Not so much. For all his ironies, and all his sympathy with Halley, Mr Baker doesn’t quite see this one. Presumably it would not be in keeping with his generally light-hearted approach to what would othewise be heart-wrenching social pathologies.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.