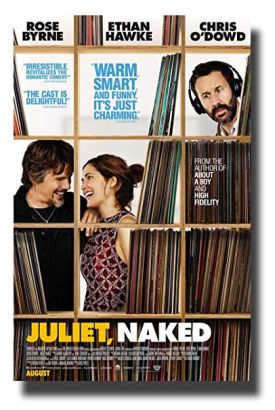

Juliet Naked

In the annals of movie titling, Juliet, Naked must deserve a special place, since there is no one in it who is named Juliet and no one in it who is naked, though we do get a glimpse of Ethan Hawke’s underpants, if that doesn’t add insult to injury. Juliet is the title of the one album made long ago by a now nearly forgotten indy rock star named Tucker Crowe (Mr Hawke) and Juliet Naked is the title given to the recently emerged demo tape on which the album was based and which is now making the rounds of Crowe’s online fan-club. But it’s not the movie-makers who deserve the credit for this coup of audience-titillation. It’s Nick Hornby, who wrote the novel of the same title on which the film was based. Those who have seen the movies based on his previous novels (High Fidelity of 2000 and About a Boy of 2002 among others) will pretty much know what to expect: basically, the difficulties encountered by selfish or nerdy young men in learning to connect with normal human beings and thus becoming more or less human themselves.

In this iteration, there are not one but two selfish males, and neither is young anymore — perhaps reflecting the ever-advancing age at which maturity may be expected to dawn in the society at large. Tucker Crowe’s number one fan and the manager of the website devoted to him is a minor Irish academic named Duncan (Chris O’Dowd) living in an English seaside town with his girlfriend, Annie (Rose Byrne), who runs a local museum, founded by her late father. Duncan’s devotion to the obscure rock star is not unrelated to that obscurity — or the fact that, after recording his one soulful album named after a woman he had loved and (apparently) lost, he suddenly and without explanation retired from performing or recording. His cult following online naturally only grew by inviting speculation and rumor, and by declining all requests for interviews.

The set-up very specifically includes the information that Annie longs for marriage and a family and Duncan — doesn’t. He affects that once-common hippyish belief — perhaps it still is common — that it would be wrong to bring children into such a wicked and presumably doomed world as ours is. Like his fanboy’s love for Tucker Crowe’s lugubrious ballads and the online fellowship his enthusiasm helps to create, this helps to justify in Duncan’s own mind his refusal to grow up, though he must be close to 40. Without giving away the whole plot, I can reveal that the redemption of Duncan from his life of childish irresponsibility takes a backseat to the ditto of Tucker Crowe himself, who turns up one day in Duncan’s and Annie’s home town and demonstrates at least the beginning of self-knowledge in response to some on-line criticism from Annie, who opened Duncan’s mail the day that the CD of Juliet Naked arrived..

My favorite moment in the film comes when Duncan, on meeting his idol, reacts badly to being told by the latter that the songs he so admires are no good. What could be more definitive than the author’s own authority? But Duncan goes off in a huff, his parting shot to Tucker being: “Art isn’t for the artist, any more than water is for the bloody plumber.” It is something of an artistic feat in itself to make a character whom we have learned to think of as being wrong about everything confound all expectation by saying something that just might be triumphantly right, though not necessarily in the way that he means it. Even bad art, that is, or “art” as trivial as most pop music is, is the artist’s gift to the world. It cannot, therefore, be up to the artist to decide what the world does with his gift or what it does with the world — any more than he can take the gift back once it is given.

In this, of course, it is like having children, who are ours but only during a continuous process of their becoming not ours anymore but the world’s. Therefore, it is probably no accident that having children is the other main theme of the film — not only in Annie’s dissatisfaction with not having them but also in Tucker’s philoprogenitive rock-star’s habit of bringing children into the world and then leaving their abandoned mothers to look after them. As with his music, Tucker wants to disclaim responsibility for what he has helped to create while at the same time remaining dimly aware that he has been wrong to do so, and the effect upon his blighted life of his having been so wrong. We can tell this because when we meet him he is at last trying to be a real father to the most recent of his offspring, a boy named Jackson (Azhy Robertson).

In the real world, if it is still possible to use that expression, ordinary people already know all this and must find it rather amusing when it strikes those who claim social or intellectual superiority on account of being successfully hip and famous with the force of revelation. Not for the first time, one wonders just how far a Nick Hornby character is a stand-in for Nick Hornby, or if he only views such selfishness and immaturity from afar and with the same sense of detachment as the rest of us. But at least we may fall back on the Bible verse about the joy that, I seem to remember, shall be in heaven over one sinner that repenteth, more than over ninety and nine just persons, which need no repentance — at least if we’re not overly resentful to think that even the rich and the famous can have happy endings.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.