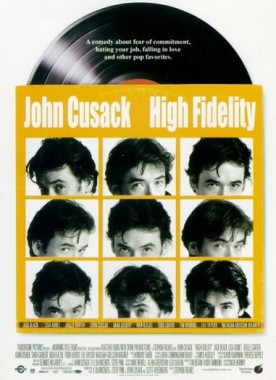

High Fidelity

There is a certain kind of modern novel that is not really a novel at all but a series of ruminations on life, the universe and everything by a narrator who is a would-be philosopher and thinly disguised stand-in for the author. The master of this sort of ruminative fiction is Richard Ford, whose novels, in spite of being deadly boring, have a considerable following among the highbrows—mainly, I guess, because highbrows these days think that Ford’s ruminations sound profound. Now the ruminative style has been translated to the silver screen in High Fidelity, Stephen Frears’s adaptation (written by D.V. DeVincentis, Steve Pink and John Cusack) of Nick Hornby’s novel. In some ways, the style is better suited to the movies than to fiction, partly because it doesn’t take so much of your time to consume it and partly because it has to know better than Ford apparently does what it is doing.

More important, in this film at least, the ruminations are better and more witty. The film begins with its tormented hero, Rob (Mr. Cusack) addressing the camera about the seeming paradox of kids’ enjoyment of listening to music mainly about unhappiness in love. If people are worried about the effect on them of seeing so many violent acts on television, what about the effect on them of listening to so much heartbreak in their music. Concluding he asks, “Did I listen to pop music because I was miserable, or was I miserable because I listened to pop music?” It is not a question meant to be answered. Rather, it marks him as connoisseur (of pop music), victim (of unspecified heartbreak) and philosopher.

The device of his directly speaking to the camera like this would soon be unbearable if it were not for the general brightness and pithiness of his observations and the witty links between them and the drama that they interrupt. For at once we learn that the source of his heartbreak is the fact that his girlfriend, Laura (Iben Hjejle), is walking out on him. Rob, listening to his sad songs, calls after her: “If you wanted to mess me up, you should have gotten here earlier!” This idea, in fact, provides such narrative forward momentum as the film possesses. Speaking urgently and intimately to the camera, Rob goes through his “top five breakups,” introducing us in dramatic vignettes to all the girlfriends who have dumped him before and asking himself and us what could be the common thread of connection between these.

The stories, both of the romances and the breakups, flash by quickly and are both funny in themselves and provide Rob with the opportunity for more self-depreciatory humor. Of Charlie (Catherine Zeta-Jones), for instance, he tells us that she was so smart as to be “out of my class.” He considers himself an intellectual middleweight—“not the smartest guy, but not the dumbest either,” and as an illustration of just what he means he says that he “read The Unbearable Lightness of Being and Love in the Time of Cholera and think I understand them.” Here, obviously, is what the administrators of the SAT now call an intellectual “striver” whom we would like to see succeed.

In between these intimate narrations, we see Rob in his everyday life as proprietor of a less-than profitable record store in Chicago in which only old fashioned vinyl discs are sold. Or, more often, not sold. He is assisted by two pals, Barry (Jack Black) and Dick (Todd Louiso) whose knowledge of pop music is as encyclopedic as his own and whose tastes as sharply defined. When a customer comes into the store asking for a record for his daughter that Barry thinks “sentimental crap” he scolds the man for corrupting his daughter’s taste and tells him to get out. Barry, a frustrated musician himself who sings with a band called Sonic Death Monkeys—assumed by everyone but him to be terrible—is a kind of counterpart of Rob’s philosopher.

Both, that is, are essentially critics who wish they were artists—just like the masters of the ruminative school themselves. But instead of being allowed to pontificate from atop their massive dignity through to the end, as they would be in a Richard Ford novel, both are knocked off their perches. Rob in particular, becomes almost a stalker and does not come off well in his comical confrontation with Laura’s new boyfriend, a wonderfully smarmy therapist called Ian (Tim Robbins). “Conflict resolution is my job,” says Ian, attempting to soothe the jealous and savagely opinionated Rob who is all but paralysed by the range of aggressive responses that his imagination plays out for us on the screen.

Such paralysis is a kind of occupational hazard for a critic and philosopher like Rob. As Nietzsche said, “Understanding stops action.” It is also related to his love life and his feelings of helplessness in the grip of his love of Laura. In the end, he is able to break out of both. As a producer he puts out the first record of some local skateboarders whose talent he discovers when he catches them shoplifting and who form a neo-punk band called the Kinky Wizards. Their record is called: “I sold my mom’s wheelchair.” Laura, fed up at last with Ian, points out, rather to Rob’s surprise, that with this record, “You, the critic, the professional appreciator put something new into the world,” and that helps to bring them together again. Even Barry, in his debut as a musician, surprisingly proves himself capable of being more accessible and likeable than he is as a critic.

But the paradox of Rob and Laura’s becoming, like their namesakes on the old “Dick Van Dyke” show, America’s idea of an ordinary married couple is that this transformation involves a final repudiation of the pop music values that Rob began by telling us have dominated his life. We have seen him throughout as obsessed with love and love’s woes as the music is, and he now professes himself “sick of thinking about it all the time.” Laura calls this “the most romantic thing I ever heard” because she realizes that it means he has grown up and grown out of the prolonged adolescence that now seems to be every American’s birthright. Maybe he realizes the same thing when he starts to understand something about adult relationships. “I never really committed to Laura,” he says to the camera. “I always had one foot out the door. . .And that’s suicide by tiny, tiny increments.

Laura herself has what amounts to a similar epiphany when she tells Rob: “I’m too tired not to be with you.”

“You mean,” says Rob, “If you had more energy we’d stay split up but, you being all wiped out and all, we stay together?”

That’s about the size of it. Perhaps growing up is just a matter of getting tired, of finally dissipating all that adolescent energy. Laura’s weariness, at any rate, is the counterpart of his. “I’m tired of the fantasy because it doesn’t really exist,” he tells her, thinking perhaps as much of the musical sort of fantasy as the romantic. “It never really delivers.” But, remarkably enough, “I never get tired of you.” That is the reality corresponding to the “fantasy” of love that all the pop songs celebrate, but somehow we know—as Rob and Laura know about their hard-won love and understanding—it won’t go in a song.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.