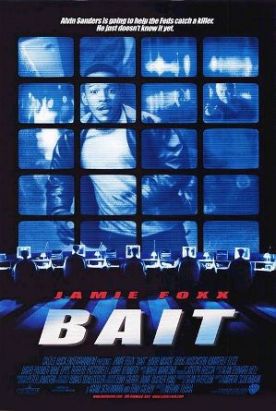

Bait

Bait, written by a committee (Andrew Scheinman, Adam Scheinman and Tony Gilroy) and directed by Antoine Fuqua, almost rises to the level of a decent movie, but of course it cannot resist (as what contemporary Hollywood movie can resist?) the temptation to over-egg the pudding. The central character is an appealing ne’er-do-well and petty thief called Alvin Sanders (Jamie Foxx) who is none too bright but who, after his arrest for attempting to steal frozen prawns from a seafood warehouse and the subsequent discovery that he is a father, tries to go straight. Unknown to him, he has had a sophisticated tracking device surgically implanted in his jaw so that a team of treasury agents can use him as bait to lure out of hiding a ruthless killer and cyber-super villain called Bristol (Douglas Hutchison) who has stolen $14 million in gold from something called the “Federal Gold Reserve, Manhattan” and whose now-dead partner—briefly Alvin’s cell-mate at Riker’s Island—was the only man who knew where the gold is hidden.

Presumably the filmmakers thought that a man’s attempt to turn himself into a decent and honest citizen would not make a sympathetic enough character. Or perhaps they were forced to adapt their script because Mr Foxx balked at his character’s being such a dork. Most likely they just thought it would appeal to the audience of 11-year olds that this and every other film now seem to be intended for. For whatever reason, the committee decided to make Alvin into a clone of every other “cool,” wisecracking hero who has strutted across the screen in the last twenty or thirty years. And in the end they make him, rather in the fashion of the allegedly homely girl who takes her glasses off and lets her hair down and is suddenly beautiful, a sort of action-hero manqué. This rather spoiled the film for me.

Nor is this the only way in which the film seeks to gratify audience expectations rather than tell a true (or true-ish) story. Alvin is given a melodramatically poverty-stricken childhood—his father, a groom at the racetrack, made so little money that he had to steal the Christmas presents for his large family and was subsequently led away in handcuffs on Christmas day—and none of the hard-edged quality of the genuine criminal. At the other extreme, the bad guy Bristol, played with a soft-spoken menace learned from John Malkovich (Hutchison even looks a bit like Malkovich), is virtually inhuman and omnicompetent in his villainy. As in other sorts of black box movies, there seems no jam that he cannot get himself out of with the help of some bit of technological wizardry that is perpetually at his fingertips. This naturally appeals to the juvenile fantasists and devotees of the romance of the machine who enjoy projecting themselves onto such powerful figures.

It also allows the film to present the federal agents as bumbling fools. To be sure, they are not so foolish, or so corrupt, as we might expect, given most of the recent cinematic depictions of FBI agents and the like. But they are seen as almost casually taking up the position of outlaw renegades, and heartlessly prepared to sacrifice poor Alvin, in order to get their man. “Mr Clenteen,” one of them says to the chief of the investigation (David Morse), “exactly how many laws are we breaking here?”

“You don’t want to know,” says Clenteen.

When one on the surveillance team is impressed, in spite of himself, with Alvin’s resolve to get a job and be a father to his child and says: “I think Alvin might make it this time,” Clenteen snaps back: “Sanders is bait….and you know what happens to bait.”

I think we are meant to see a softening in his attitude, as the rest of the team’s growing affection for Alvin’s good nature rubs off on him. But this foundation of what might have been a good movie is undermined by the need to keep Alvin hip and full of “attitude” towards The Man. When Clenteen ultimately congratulates him because he “did a good thing for your country,” (needless to say, there is no hint anywhere in the film of the public spirit this implies), Alvin shoots back: “We need to talk about what my country’s going to do for me.” It is one measure of how far we have sunk without even knowing it that a remark like this is apparently thought to redound not to the discredit but to the credit of the speaker.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.