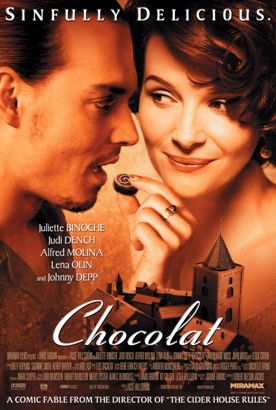

Chocolat

Naturally, I had hoped to be able to avoid going to see Lasse Hallström’s sickly-sweet Chocolat. After The Cider House Rules, indeed, I hoped never to have to see another movie by Hallström. But when Chocolat was nominated for a Best Picture Oscar I resigned myself to the necessity of having to waste two hours on the wretched thing. Having done so, I wish I could say I was pleasantly surprised by it, but the movie was, if anything, worse than I had supposed. Like Cider House Rules, it was a sort of reverse moral tale: a soothing reassurance to the Sybaritic culture of Hollywood that it is quite right to live for pleasure, since those who would put moral obstacles in the way of its doing so are petty, joyless, narrow-minded, bigoted, superstitious hypocrites and wife-beaters. By contrast, people like them are brave, intelligent, compassionate and full of joie de vivre.

If the movie hadn’t been conceived of as a broadside in the “culture war,” you might be inclined to think it almost by itself enough of a provocation to start one. But then you would have to ask yourself: Who would it be fighting against? True, there are scattered through America’s rural and suburban countryside a fair number of people whom the left refer to as “the Christian right.” Though few of these are ascetics, it would be fair to say that they take, on the whole, a less than entirely benevolent view of self-indulgence. But there can be few places even in America today—and none at all in France, where the film is set—where the Christians are so socially dominant as to be able to ostracize and persecute a single-mother who doesn’t go to church and sells chocolate during Lent.

That, of course, is why the fable is set in 1960, which was almost the last moment at which the traditional French Catholic culture could plausibly be represented as having had any social force at all, even in an out-of-the-way rural village. “Once upon a time,” the voiceover begins, “there was a French village whose people believed in tranquillité—tranquility. . .If you lived in this village, you knew what was expected of you. You knew your place in the scheme of things. And if you happened to forget, someone would remind you. . .If you saw something you weren’t supposed to see, you looked away. If by chance your hopes were disappointed, you learned never to ask for more. So, through good times and bad, famine and feast, the villagers held on to their traditions, until one day. . .”

Well, one day the charming Vianne (Juliette Binoche) and her young daughter Anouk (Victoire Thivisol) came to town and more or less effortlessly, by feeding people chocolate prepared according to ancient Mayan recipes, pushed over the whole rotten edifice of tradition and Catholicism and tranquillité. As Homer Simpson would say: Stupid tranquility! Likewise we are invited to cluck our tongues and shake our heads over the fact that the village aristocrat and leading citizen, the Comte de Reynaud (Alfred Molina) is said to have “trusted the wisdom of generations past” and to have lived his life according to the principles of “hard work, modesty, self-discipline.” Well! Did you ever?

Such Western virtues are inevitably set against the secrets of the Maya Indian, discovered in the 1920s by Vianne’s father Georges, an apothecary, who learned from the Indians that cacao “had the power to unlock hidden yearnings.” His own “hidden yearnings” were for carnal congress with a dusky Indian maiden, who was Vianne’s mother, though both Vianne and her daughter must have inherited Georges’s pasty white complexion. Why it should have taken a special potion to bring out such “hidden yearnings” when so many others manage to bring them out unmedicated we are never told. But the story is obviously meant to appeal to the reverence that yearnings of any sort elicit from the Hollywood culture. There is also an overlay of feminism in showing the Indian maiden and Vianne, as later Vianne and her own daughter, liberated from masculine supervision and wandering the earth alone, dressed in their matching red riding hoods, to minister to hidden yearnings more promiscuously.

But why does Hallström feel that he has to re-fight this battle which was won so long ago and so decisively by his own side? Are there so many people living lives of hard work, modesty and self-discipline—to say nothing of tranquility—that we must be warned against them and the dangers they pose to our precious pleasures? The young village priest, Père Henri (Hugh O’Conor) is shown as having “a weakness for American music”—in particular Elvis Presley’s “Hound Dog”— which has to be suppressed by the stern moralism of the Count, but it only takes that much of a hint at the cultural forces operating just over the horizon in 1960 to remind us of the extent to which the village’s tranquillité, and that of the rest of the Western world, was about to be wiped out forever.

What more does Hallström want? I think the answer is that he wants to reassure himself and those who believe as he does that they are not only successful but that they were right, that their success was justified. This betokens a certain anxiety on that head, I suppose, but then that is true of all mythmakers. If they really thought they were right they would hardly expend so much time and effort trying to demonstrate that they were. Thus Hallström has the count tell Vianne: “The first Comte de Reynaud expelled the Huguenots from this village. You and your chocolates present a far lesser challenge.” Huh? The victory of the pleasure lovers is another chapter in the long struggle for religious freedom? Who knew? The fatuousness of such a point of view is only what we expect from the corrupt and self-congratulatory culture of Hollywood.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.