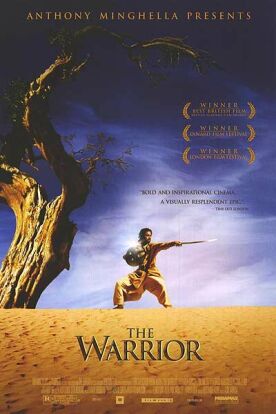

Warrior, The

The Warrior, written and directed by Asif Kapadia, a British director of Indian heritage, is now four years old, but it is only just getting a release in the US. This is long overdue. It is a beautiful film with the mythic force of a parable, and its simple but engaging story is told in a slow, spacious, rather oriental style. Contributing to the effect is the fact that it is set in a quasi-mythic time and place: an indigenous, pre-modern despotism in the desert of Rajasthan. This is the sort of place where the despot’s factor sits barefoot and crosslegged under an awning to receive the tribute of the surrounding villages. When the elderly representative of a village called Taramy pleads that it has been drought-stricken and is unable to pay the full amount, the factor orders his head struck off forthwith. For him it seems a matter of no more moment than swatting a fly, and it can be hardly more so for Lafcadia (Irfan Khan), the man who is instructed to carry out the sentence and who subsequently becomes the hero of The Warrior.

He and three or four other warriors — perhaps the whole of the despot’s military strength — are then sent to burn Taramy and put it to the sword. That kind of thing is all in the day’s work for them, we gather, and it never seems to occur to anyone, either the warriors or their victims, that they might do anything but rape and murder and burn in accordance with the despot’s orders. Yet in the midst of the sack of the unfortunate village, Lafcadia is stopped in his tracks when he turns his sword on a little girl, Mira (Sunita Sharma), who happens to be wearing an amulet belonging to his young son, Katiba (Puru Chibber). He had given it to her when she had done him a small kindness. The shock of the warrior’s recognition of the amulet and his moral transformation is represented cinematically by an answering transformation of everything in the picture except the two human figures in the tableau, the one with his sword point held ready to strike at the other’s throat. They remain frozen in that attitude while the tumbledown desert town of Taramy magically becomes a wild mountain scene blanketed in snow.

It is as if a lifetime has passed in an instant — the whole of the life, perhaps, that has brought Lafcadia down from his mountain home, Kullu, in the first place to seek service as a warrior for the despot. When the scene shifts again to Taramy, Lafcadia lets his sword drop and then looks down to see snow still under his shoes. He vows never to lift his sword again and announces to Katiba that they are to return to Kullu. For him it is the good place, the holy city, the locus of peace and moral purity and redemption. The visual contrast of desert and mountain, sand and snow, becomes a running theme of the film and reinforces our sense of the polarity between the world of the despot and his warriors on the one hand and the poor peasants they prey upon on the other — and so between evil and good, death and life. That visual presence helps to create our sense of the permanence, the elemental quality of such polarities. They are obviously not to be lightly disregarded.

So it is that, at the news Lafcadia has deserted him, the despot says to one of the remaining warriors: “No one leaves my service. Bring me his head by dawn, or I will have yours.” It would have been easy for the film to turn altogether moralistic about this: to extend the imagery of good and evil to the ex-warrior and his pursuer, respectively, but I don’t think this is The Warrior’s purpose. We can hardly watch it without reading some such meaning into the film, so completely is our own culture committed to the ways of peace and non-violence and against the way of the warrior, but Kapadia is more interested in his hero’s personal search for redemption.The cruel world of the despot, that is, is not somebody’s bad choice — not even the despot’s — and Lafcadia’s decision to leave it a good one. Both are simply facts of life, eternally present in the world like the desert and the mountains, and the choices that are made and the terrible sacrifices they entail both have an air of inevitability about them.

Instead of moralizing, then, the movie means to create in us a sense of that oriental duality between the worlds of the flesh and the spirit — and of the magnetic repulsion that must always exist between them. Even when the warrior is joined on his journey by a young scamp and thief called Riaz (Noor Mani) or when he tries to help an old blind woman (Damayanti Marfatia) on her way to a holy lake in the mountains and is spurned by her after she touches him and says that “there’s blood written in your face” — even these events do not imply moral approval or disapproval. They only illustrate what it means to move back and forth between the two worlds, as people always have done and always will do. Finally, the film’s use of visual contrast, its dreamlike feel and flirtation with magic and prophecy all go to suggest that the only question that matters is which of the two worlds of desert or mountain, of war or peace, of striving or of retreat and contemplation is the more real. And the answer is by no means to be taken for granted.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.