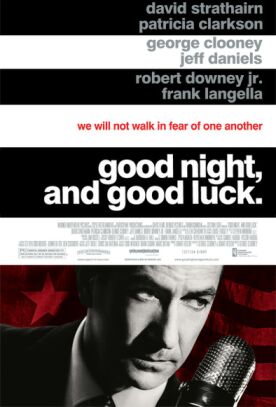

Good Night and Good Luck

Why I should have expected anything other than an exercise in media triumphalism from Good Night and Good Luck, I don’t know, but I did. Silly me. If I had seen the advertising tag-line before I saw the movie, I’d have known better. “In A Nation Terrorized By Its Own Government, One Man Dared to Tell The Truth.” What nation would that be, I wonder? Oh, right, of course it’s the United States of Amerika. And such nonsense is not only in the tag-line. The film’s hero, Edward R. Murrow (David Strathairn), a once famous CBS newsman, explains his broadcast attack on Senator Joseph McCarthy in March of 1954 by saying he’s “going to go after him because the terror is right here in this room.” Yeah, right. The real Murrow made his name reporting to Americans on the Blitz in London. It’s a little hard to believe that he didn’t have a better idea than this of what “terror” meant.

At any rate, the film’s director, George Clooney, and his co-writer, Grant Heslov, don’t. They have completely and uncritically bought into the official Hollywood version of the McCarthy era. It’s hardly surprising, but it’s quite false. Not by the wildest caprice of imagination was “A Nation Terrorized” by McCarthy. A few screenwriters, actors and directors with a strong sense of their own entitlement to keep on writing, acting and directing were denied that opportunity. Some diplomats, military men and other government officials also lost their jobs. Some were not hired. Most of those who were seriously affected had been and in some cases still were communists or communist sympathizers — which in those days meant agents or would-be agents of Joseph Stalin or his heirs, foreign dictators whose massive military might was geared for war against America, whose proxies were or had recently been killing American soldiers in Korea and who were responsible for what at the time were the greatest mass-murders in history.

In that context, to talk of the junior senator from Wisconsin as “terrorizing” anybody is a form of hysteria. There are plenty of things to regret about the career of Senator McCarthy, but to regard him as a terrorist amounts to a wilful refusal to understand “The Truth” that the film and the media culture it represents here characteristically claim as their own property. Murrow and his producer at the network, Fred Friendly (Mr Clooney), are presented as a sort of Woodward and Bernstein avant la lettre. They’re up against McCarthy, all right, but McCarthy himself never appears except on the television screen. Nor does anything else outside the claustrophobic CBS newsroom. The only human drama the film bothers to present us with comes as Murrow and Friendly attempt to persuade William Paley (Frank Langella), the President of CBS, to let them go on with their political campaign in spite of the hostility of advertisers.

Spoiler alert! They are successful.

Because his heroes are so perfect — always right, as McCarthy is always wrong — Mr Clooney must have seen the need to qualify his admiration in some way, lest his film become mere hagiography. This he does, or rather tries to do, by stressing its period feel. Not only is it in black-and-white, so that it will blend in easily with the kinescopes of the period that he uses with some frequency (and exclusively to represent Senator McCarthy), but he portrays people as being of their times in ways calculated to make them stand out to us. They are constantly smoking and drinking, for example, and their attitudes towards women in the workplace — here represented mainly by Patricia Clarkson as Shirley Wershba — are gratifyingly Neanderthal.

Scene: a Manhattan bar in the small hours. Murrow and Friendly and the whole CBS staff are knocking them back after his famous broadcast attack on McCarthy, waiting to see what the papers will say about it. The air is thick with smoke and male camaraderie. “Shirley, hon,” says Murrow to the only woman present, “will you just go across the street and get the early editions?”

In another scene we see Murrow interviewing Liberace and asking him if there is any immediate prospect of his marrying and settling down. It is perhaps not quite clear whether we are meant to laugh at Murrow’s naïveté or at the hypocrisies of the time which made it necessary to keep up the pretense that everybody in the public eye was heterosexual. There is also the strange subplot about the discovery of the secret marriage — because CBS had a policy prohibiting two of its employees from being married to each other — between Shirley and her husband Joe (Robert Downey Jr). What, I wonder, is the point of this? That CBS had issued such a puritanical edict on account of McCarthy? All these things are not really humanizing details. Even when we see an actual commercial for Kent cigarettes which stresses that the manufacturer has chosen Murrow’s show for its advertising because the people who watch it are more intelligent than the average, it is not really a fault of Murrow’s so much as a way of being patronizing towards his period.

But the movie itself is evidence that we have no right to patronize. For the questions that anyone without Hollywood’s and the media’s vested interests in self-mythologizing would want to have answered — and that the real-life 1950s, for all their benightedness, were obsessive about trying to answer — are these: were there, in fact, any communists in Hollywood, the media or the government and were they a real danger to the Republic? These questions the movie never thinks it worth its while to ask, let alone answer, save in one brief scene where Shirley and Joe are in bed and one of them asks: “What if we’re wrong? Can we be sure that we’re not going to look back and see that we were protecting the wrong side? Happily for them, they decide that they can be sure.

One line of Murrow’s attack on McCarthy stands out for a Truth that is more, one hopes, than mere advertising hype. It is that “mature Americans can engage in the clash of ideas without being contaminated.” That may have been true in the 1950s. But a movie like this one, which feels it necessary to protect us from any genuine controversy, suggests that it is so no longer.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.