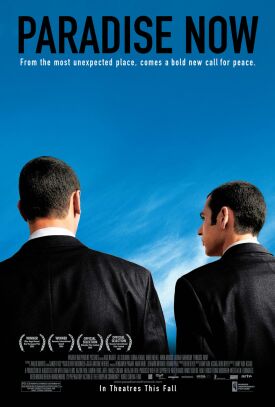

Humanized Without Honor

From The American Spectator“Politics aside,” wrote the New York Times critic, Stephen Holden, of Hany Abu-Assad’s Paradise Now, “the movie is a superior thriller whose shrewdly inserted plot twists and emotional wrinkles are calculated to put your heart in your throat and keep it there.” Politics aside? What is there besides politics for this “superior thriller” to thrill us with? It was mildly heartening to see that the families of three Israelis killed by a Palestinian suicide bomber just three years ago on Oscar night protested to the Motion Picture Academy about the nomination of this vile, terrorist-glorifying movie as Best Foreign Film, but their protests were hardly noticed. In any properly organized society, this nomination would be a scandal, but the media have been too busy lately desperately trying to strike a spark of scandal in the wet tinder of Dick Cheney’s hunting accident or the Bush administration’s selling out our ports’ security to a pack of A-rabs or its failure to stop Hurricane Katrina from devastating New Orleans to pay any attention to the movie industry’s kudos for a cinematic apology for murderers.

I particularly liked the comment of the father of Tal Kehrmann, a 17-year-old girl who died on a bus just like the one in the movie. The movie ends just before the bus is blown up, and the consequences of the act of terrorism are tastefully omitted. “I felt obligated to see the movie,” said Tal’s father. “But it doesn’t show the end, it just fades to white. I’m living at the end, and it’s definitely not paradise.” He and the other families added an “extra page” to the screenplay, describing the human misery the bombing caused, in the form of a full-page ad in Variety. It’s a good way to show us the political point of the film’s ending where it does.

“Given the explosive political climate in the Middle East,” Mr Holden went on, “humanizing suicide bombers in a movie risks offending some viewers in the same way that humanizing Hitler does. Demons make more convenient villains than complicated people with their complicated motives.” This is a typical liberal misunderstanding. What bothers those of us who are bothered by Paradise Now is not that it humanizes suicide bombers but that the effort to humanize them creates a moral disproportion. The bombers’ humanity is all we see, and it grows so large that it crowds out the monstrousness of their deeds. The subtext of such a film is therefore to excuse those deeds. In other words, it humanizes the bombers only at the cost of dehumanizing Tal Kehrmann and others of their victims.

Tout comprendre c’est tout pardonner

, as the French understandingly put it. But understanding can be over-rated, particularly when the point of it is not just to pardon evil acts but to make us forget that they are evil. Ultimately, understanding why such an act was performed is irrelevant to the irreducible fact of its evil. The movies make us forget this, not as a by-product of their power to humanize but as their very reason for being made. The humanizing isn’t the end but the means to the end, and the end is to excuse. Humanity is everywhere around us. The reason for picking this particular morsel of humanity to celebrate is precisely so as to minimize the importance of an inhuman deed. Hence the movie-makers and their apologists, like Mr Holden, are being disingenuous when they say the movie justifies itself by humanizing its subjects. The first question to be asked is not whether humanity is represented in the case of the suicide bombers but whether it is humanity which is the salient moral fact about them. To say that it is, which is what such movies in effect do say, is to trivialize mass murder.

Paradise Now

is a good illustration of the hopelessness of the movie culture when it comes to dealing with serious political subjects. The same lopsided disproportion between the moral elephant in the middle of the room and their focus on the odd bit of humanity trying to get our attention in a corner is even more striking in Sorry, Haters, by Jeff Stanzler. There, Islamic terrorism is a mere backdrop to the story of a crazy woman (Robin Wright Penn) driven barking mad by a combination of loneliness, self-hatred and obsessive jealousy of her friend and boss (Sandra Oh). As a result, the film raises the question of whether or not Islamic terrorism even exists apart from the fear of it which has resulted in the shipping off to Guantánamo of the innocent brother of Ashade (Abdellatif Kechiche). Certainly Ashade and the other Muslims in the film are very far from being terrorists. It is only the hope that they might be persuaded by her to commit terrorist acts which animates Phoebe, Mrs Penn’s crazy lady. She tries to explain to Ashade why she falsely denounced him and his brother’s wife to the police when he failed to turn terrorist at her bidding. “It was wrong what I did to you and Eloise,” she says, but — referring to 9/11 — “that day I was not a nobody. I wasn’t powerless, because everybody was powerless. I just wanted that day back.”

Once again, the effort to humanize the act of a moral monster by means of psychological explanations produces a ludicrous sense of disproportion — as if the petty jealousies and feelings that loom so large in poor Phoebe’s delusional world could ever be weighed equally in any plausible moral scale with the loss of over 3000 lives. What about humanizing some of them? That Mr Stanzler presumably cannot see this dreadful, politically-inspired moral imbalance, any more than the Academy voters who nominated Mr Abu-Assad’s film for an Oscar could see it, is partly a consequence of the political monoculture of the movie industry and partly of the illusion of knowledge created by therapeutic analysis. The “understanding” which comes from putting an individual human life and psychology under the cinematic microscope, is gained by wrenching that life out of its larger social and moral context. In this sense it doesn’t matter if we pardon or condemn Phoebe or the suicide bombers in Paradise Now. The point is that the humanizing process so admired by Mr Holden dehumanizes and renders insignificant their victims and so distorts the moral picture that any genuinely humane way of looking at them would require.

|

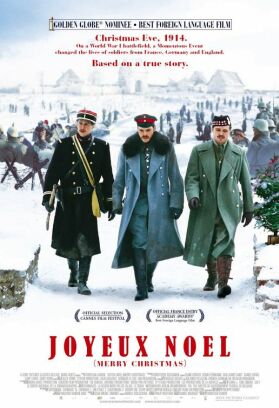

That distortion is not accidental. It is the point. For by its means we can reduce a complex moral matter to something much simpler and more manageable. The film-makers and their apologists who cite “nuance” and moral complexity as their justification and insist that their critics are guilty of “demonization” are often themselves guilty of such thinking. Just look at Joyeux Noel by Christian Carion, which offers a fictionalized version of the Christmas truce that took place on a part of the Western Front in France in 1914. The human scale of the film is very interesting, even moving. We watch the Germans, French and Scots, most of whom we must suppose to be doomed to fall in the nearly four years of carnage still to come in World War I, climb out of their trenches for a few hours and treat their prospective killers as human beings. But of course M. Carion cannot leave it at that. He must stick his political oar in by hyping the bloodthirstiness and unnuanced thinking of the superior officers and even a bishop — what on earth is he doing in the trenches? — who put a stop to the truce. Likewise, he begins the film with vignettes of German, French and British school-boys reeling off, parrot-like, patriotic slogans which each demonizes his country’s enemies.

We get it, for heaven’s sake! The Manichean logic which treats one’s own side as “the children of God” (as the Bishop puts it) and the enemy as the children of darkness is wrong and simple-minded and what must have kept these men killing each other so assiduously for so long. But isn’t that kind of heavy-handed point-scoring itself just a little simple-minded? The movie itself divides the world into good people and bad people, only instead of drawing the boundary between them along national lines, it treats the leaders who believe in the war as the bad and everybody else as the good. Where’s the nuance in that? It is frankly unbelievable to suppose that it was only wicked generals and bishops and politicians that kept the war going.

This is politics reduced to the Lennonist “Give peace a chance” level, or Rodney King’s “Can’t we all just get along.” Well, no we can’t, as a matter of fact. All of human history shows us this. The soldiers of World War I died in their millions not because they were too stupid to know any better, or too timorous to rise up against their masters, but because they believed in something — I would call it honor — that was more important than their individual humanity. Not that you’d know that from this film, or indeed almost any other of the last 30 years. Just once it would be nice to see a movie that knew so much about human beings as that, or that understood such a thing as honor even existed to be put into the scale along with humanity and compassion. Now there would be something for “nuance” to get its teeth into!

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.