Argo

Ben Affleck’s Argo is, in a great Hollywood tradition, a movie about movies more than what it is ostensibly about, which is a based-on-fact story of international intrigue and derring-do. Mr Affleck directs and also plays the CIA agent Tony Mendez who was given the job of exfiltrating six American diplomats hiding out in the Canadian ambassador’s residence in Teheran after the invasion of the US embassy by an Iranian mob and the taking hostage of 52 of their colleagues. The better-known hostage story, which dragged on for 14 months and ended with the inauguration of President Reagan in January of 1981, offers little for a movie dramatization to bid with for an American movie audience’s cheers, but those who were sheltered for three months by the Canadians presented a more promising scenario — not only did they put one over on the Iranians, but they did it with a wacky stratagem worthy of screwball comedy.

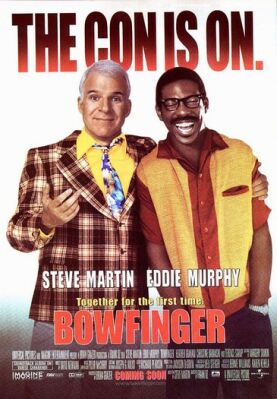

When Mr Mendez turned up in Teheran, it was with a cover story in which the Canadians’ “houseguests” were said to be part of a Canadian film crew scouting locations for a science fiction B-picture — presumably the Iranians would not have known that, as such, its budget was unlikely to have run to foreign location shooting — to be called Argo. The CIA had got the guy who did the prosethetics for Planet of the Apes, John Chambers (John Goodman), on board to form a front company, and the movie version adds a delightfully profane Alan Arkin as the fictional producer Lester Siegel who, as a fake himself, becomes the spokesman for Hollywood fakery. His is the best line in the picture when he explains to Mr Affleck’s Tony Mendez why he was such a bad husband and father. “It’s a bull***t business, like coal mining; you come home to your wife and kids, and you can’t wash it off.”

As history, Argo (the real, not the fictional movie) makes a good thriller. Politically correct Hollywood finds it obligatory to insert a voiceover framing device explaining that, after thousands of years of monarchy, the Iranians found a people’s champion named Mossadegh who was to have taken back Iran’s oil wealth (from exploitative multinational oil companies, as we will understand) and returned it to the Iranians until he was overthrown by an Anglo-American sponsored coup in 1953, which installed the corrupt Shah, Reza Pahlavi, in his stead. The Shah is then said to have lived in opulence and luxury while — following the tyrant’s script — “the people starved.” Thus, when we see immediately following scenes of Iranian revolutionaries breaking into the U.S. embassy and taking our diplomats hostage — a mixture of dramatization and archive footage — we are well prepared to believe the State Department official who says, “We did it to them first.”

Nonsense. This is a familiar left-wing history which is informed by Leninist dogma about the exploitation by Western “imperialism” of less developed countries, updated to include the racial dimension to the process hypothesized by the late Edward Said. Thus when Mr Affleck’s character approaches a Turkish official with his account of the fake movie and the fake location scouting in the Near and Middle East, the latter says to him with palpable contempt in his voice, “Ah, the exotic Orient: snake charmers, magic carpets.” To me, that line is way too obviously dragged in by the ears from Said’s “progressive” classic, Orientalism, first published only a year earlier and read mainly in Western academic circles, to ring true in this context. Besides, the childish mythology being peddled by Argo has nothing to do with the Arabian Nights but is obviously stamped, like everything else about the fictional as about the real movie, “Made in America.”

There is a certain irony about the fact that the movie’s simplistic left-wing politics is part of a more general effort on the part of the film to portray Americans as simplistic right-wing ignoramuses, naive and bumbling in their interactions with the Third World — which is not to say that some of us weren’t. Another part of the historical context that Argo wants to show us comes in snippets of contemporary TV interviews with ordinary Americans that look as if they’re genuine and express robust and bloodthirsty views as to what they would like to do to Khomeini. We are also given a clip from a period interview of the Ayatollah himself by Mike Wallace in which the latter, almost as innocent as TV’s amateur gunboat diplomatists, asks the imam (with an elaborately polite “forgive me: his words, not mine”) what he thinks of Anwar Sadat’s having described him as “a lunatic.” The lunatic’s reply is not recorded.

One of the everyman TV interviewees compares himself to the man in Network (he remembers the name of the movie but not the actor or his character) who says he’s “mad as hell” and “not going to take it anymore.” I imagine that this is to remind us of the extent to which the movies have always provided us with a context for our diplomatic interactions with the rest of the world. At one point Mr Arkin’s Lester Siegel says of the hostage crisis: “John Wayne’s in the ground six months and this is what’s left of America.” One supposes that he is meant to be speaking only half in jest. At any rate, he provides us with a reminder of the older kind of Hollywood portrait of American power, and the more up-to-date film-makers may even be indulging themselves in a note of genuine regret at its passing — in reality well in advance of John Wayne’s.

But the naiveté there is Hollywood’s and not America’s. It’s hard to escape the impression that this is in order to make the point that in 1979 Americans had not yet realized the extent to which they had lost standing in the world. They are living in a dream world, but one not all that different from the real world of 1953, when the global reach and prestige of American power was such as to swat away troublesome foreigners the way Mossadegh was swatted away. That, the decline of American power in the world in the quarter century between the overthrow of Mossadegh and the Iranian Islamic revolution that overthrew the Shah is the real context — and subtext — of the film, and not the left-wing caricature.

The authority we once exercised over and the discipline we could once impose on other countries — for their own good as much as ours — was gone by the late 1970s, which is why the hostage-takers were emboldened to do what they did. Moreover, it was at least as much respect for Ronald Reagan’s promise to re-assert American might in the world as it was the revolutionaries’ animus against Jimmy Carter that made them release their hostages when they did. That’s what makes putting the real-life Jimmy, taking credit for the rescue, into the movie in voiceover at the very end strike such a false note. Having established the tragi-comical nature of the whole affair for the previous two hours, it is a little late for Mr Affleck and his good friend Mr Carter to try to strike the heroic pose at this point. Those of us who lived through the period will remember which view of the miserable business is the more true-to-life.

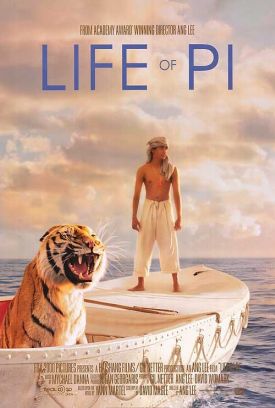

One scene is crucial to our understanding not just of the film but to what it stands for in the history of American relations with the rest of the world. In real life, the operation seems to have remained undetected by the Iranians, but Mr Affleck, working from a script by Chris Terrio, interposes various fictional obstacles to its success in order to create some suspense. One involves a confrontation between the six would-be escapers (plus their CIA escort) and a suspicious paramilitary guard at the airport who delays their departure by raising questions about the fake film, though he doesn’t know it’s a fake. At this point, the Farsi-speaking diplomat who had seemed to be the most frightened and pessimistic of the Americans — and the most skeptical about the whole improbable CIA cover story — whips out the cartoon storyboards of the fictional Argo and enthusiastically relates its preposterous story, complete with the sort of sound effects a ten-year-old might supply, to the rapt revolutionary.

It’s not unwarranted for the movie business to think that American popular culture has conquered the world where American military and diplomatic power has failed, but I wonder what the world will think of its bargain on this showing? The scene in which Lester Siegel and John Chambers go through a pile of scripts looking for one just bad enough to seem plausible is reminiscent of the comparable scene in The Producers where Zero Mostel and Gene Wilder as the eponymous producers, Max Bialystock and Leopold Bloom, do the same with equally fraudulent intentions. As in that film, we are meant to sympathize with the fraud. The difference is that The Producers depended on the (mistaken) expectation of the audience’s good taste in rejecting the awful Springtime for Hitler, whereas now we believe that the artistic nullity of this extraterrestrial fantasy is exactly what the international audience wants and can’t get enough of. I wonder if they’ll appreciate being treated as just like American teenagers any more than they did being seen by those old-timey Yanks as exotic orientals?

All this is not to say that the tale Argo has to tell is not exciting and gripping stuff, and even patriotic in an old-fashioned way. For all the hedging about our allegedly imperial past (and present), there is never any suggestion that we should not root for our guys to pull off their ruse and escape from the ruthless and bloodthirsty foreigners. In this way the real Argo is also a tribute to the fictional Argo. Looking at the world in simplistic, black-and-white terms is what Hollywood does and, therefore, it is what the success of America’s popular culture is built on. This makes America’s diplomatic history, as well as the left wing reaction to it which the film dutifully records, more understandable. Yet another framing device has Tony Mendez estranged at the beginning from his wife and son — the boy’s enthusiasm for Planet of the Apes is what gives him the idea for the subterfuge — and reunited with them at the end. Why? I think because the belated emphasis on home and its reassuring comforts helps point the contrast with the big scary world in which the U.S., as many of us first realized in 1979-80, cannot throw its weight around as it once did. Even Ben Affleck can be at least a little sorry about that.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.