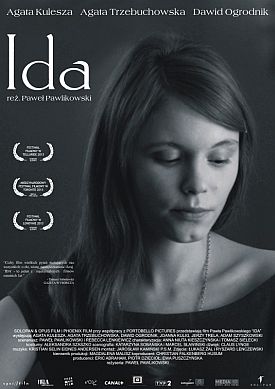

Ida

It’s hard to imagine anything more different from Pawel Pawlikowski’s wonderful My Summer of Love (2005) than his new film, but Ida is just as wonderful in its own way. It is essentially a meditation on and unpicking of a paradox, that of a Jewish nun, as a kind of synecdoche for the Polish experience of World War II and its aftermath. The burden of the past always weighs heavily on those who try, and the victims of those who try, to remake the world, and the past of Poland, subjugated by both the Nazi and the Communist attempts at reinvention of European reality, is particularly burdensome. Set in 1961 and shot in black-and-white and a 4:3 aspect ratio to make it look rather like a low budget “art film” of the same period, Ida tells the story of eighteen-year-old novitiate Anna (Agata Trzebuchowska), an orphan who has been raised in a convent and is on the point of taking her vows, who suddenly discovers that she is Jewish and that her birth name was Ida. She learns this from an aunt, Wanda (Agata Kulesza), a state prosecutor under the communist regime of Wladyslaw Gomulka.

Wanda has never hitherto wanted to have anything to do with her niece, and it is not entirely clear why she has now changed her mind. It seems to have something to do with preventing Anna from taking her vows without knowing her own background. As Wanda is a heavy drinker and sexually promiscuous, she also asks why the girl should be prepared to promise to sacrifice what she, Wanda, regards as such indispensible experiences without really knowing what they are. When Ida/Anna asks to be taken to see her family’s farm — like so many other victims of the period they are assumed to have no graves — the aunt is able to oblige since, as a state functionary, she owns a car. The movie then becomes a weird recapitulation of a classic cinematic road trip, during the course of which both women experience things they had never expected to experience and at the end of which the fate of Ida’s parents is revealed. Suffice it to say that they were killed neither by Nazis nor by Communists.

The chief virtues of the film are the painterly quality of the images of a bleak Polish landscape, dominated by louring grey skies, as photographed by a stationary camera in long takes and with very little cutting. Like a John Ford Western, Ida seeks to make a moral point and even, perhaps, a religious one, by showing its characters as dwarfed by their surroundings. The movie’s visual spareness and austerity also echo its moral standoffishness. Mr Pawlikowski is content to tell his sad story without any hint of editorializing, either morally or emotionally. These things happened. As someone says when Wanda starts trying to refresh local memories about her and Ida’s family, “We had a lot of Jews around here.” And, he might have added, a lot of people who behaved in ways they don’t like to remember now. Their attitude is like that of Wanda herself when she says that, as a state prosecutor for the communist regime, she has sent many men to their deaths. “What men?” she is asked.

“Enemies of the people.”

This approach to the material may seem at first glance to be a moral abdication, but I think the refusal to judge is also a kind of moral statement. The morality at issue is not complicated or difficult or in dispute, and the guilty recognize their own guilt along with the innocent. When that is the case and there is nothing to be done, there is also nothing to be preached and nothing to be self-righteous about. It becomes an act of humility and respect as well as a kind of witness to historical reality to decline the temptation to assert one’s own moral superiority by superfluous judgements. Wanda’s complicity with the Communist régime has taught her the sort of moral reticence that is the one thing she can pass on, along with a bit of the family’s history, to her innocent niece.

In the end Mr Pawlikowski very cleverly contrasts the historical contingency of “life” with the sort of non-life that the convent represents, at least to those outside it. And as the extraordinary-looking Ms Trzebuchowska is said to have been a civilian, picked from the crowd at a Polish café and without any ambitions to be an actress, her detachment from the profession and the movie culture resonates with that of her character from that of Poland’s secular life in the 1960s. In a way, the film could be seen as an apologia for monasticism as the only sane response to life in a barbarous age. But it doesn’t let us off that easily either, since it never quite allows us to suppose that there are any ages, even that of what seem in retrospect to have been the last century’s most placid and pacific years, that are not barbarous.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.