Me Before You

One of the most depressing statistics I have ever read came out of a survey of British funeral directors a few years ago which asked them what, in their experience, was the most popular musical request to serenade the passage of the deceased to the next world. Top of the death pops, it found, was Frank Sinatra’s celebrated rendition of Paul Anka’s “My Way.” This was hardly surprising, I suppose, in light of the song’s 75 weeks in the UK’s Top 40 back in the 1970s, which is still a record according to Wikipedia, but what kind of person wants to be remembered like that? Every time I can’t avoid listening to this dreadful ditty I think of the complementary version that, for some reason, we never get to hear from the nearest and dearest of the song’s proud persona — the people who, however unwillingly, got the thankless job of making “My Way” possible for him. I think their song might sound rather different.

But if “My Way” sounds like the height of vulgarity to some of us old- fashioned types, we must admit that it is we who are out of step with the times. Nowadays, the bumptiousness of a Donald Trump or a Mohammed Ali is considered just part of his charm, and the older, Christian view that we owe our lives to our Creator and so are obliged to do it His way and not our own that is the mark of the base vulgar.

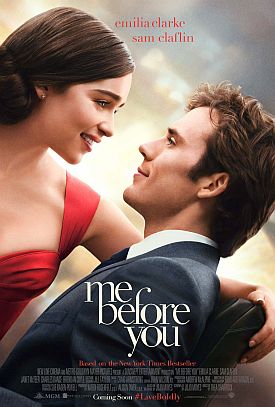

Another, more subtle example of this inversion of traditional ideas of personal honor is to be found in the movie Me Before You, adapted from her own novel by JoJo Moyes and directed by Thea Sharrock. Attempting to review this picture, I find myself in something of a dilemma. Two dilemmas, actually. The first is that, though all primed and ready to be savage to it, I find that most critics have already trashed it — which makes me, perhaps perversely, inclined to defend it against what looks to me like their determination to find things to hate. It’s not so bad as they say, folks. Or, to be more precise, it’s not bad for the reasons they say it is, which mostly have to do either with their claim to have seen it all before or else the unlikeability of one or both of the two main characters or else the excessive sentimentality they see in an ending which seems to be sending the audience (though not the critics) home in floods of tears.

The ending is the other dilemma, since I find that I am unable to write intelligibly about the film without giving it away. So big-time spoiler alert. This may be one time you want to see the movie first and read the review afterwards. Chances are that if you’re interested enough to want to see the movie, you already know how it ends anyway. Suffice it to say that the hero, Will Traynor (Sam Claflin), is transformed overnight from a high-flying businessman with a taste for extreme sports into a tetraplegic after being hit by a motorcycle on a rainy London street. Thereafter, living in a specially adapted annex to “the Castle,” owned by his upper-class parents (Janet McTeer and Charles Dance), he retains of his old life only bitter memories and the arrogant determination to have things, including his own death, his way.

Meanwhile, during the six months grace he gives his mother before doing away with himself at the Dignitas clinic in Switzerland, he undertakes to play Pygmalion to his feisty, working-class caregiver, Louisa Clark (Emilia Clarke). Of course she falls in love with him and he, insofar as he can love anyone but himself, with her. Equally of course, she decides to show him that life can be worth living, even in his lamentable state, and thereby to prevent the dreadful end he has planned for himself. That all sounds straightforward enough, and the scenes of their gradual growth of affection after a rocky start are actually quite affecting. But as with so many other British films and novels, the subtext of social class works its way in as a central theme — though not to this film’s benefit.

For Will introduces Lou to what they used to call arts and ideas “above her station” in life — things like subtitled movies and Mozart — while the station itself remains more or less constantly before us in the shape of Lou’s non-working, working-class family whom she is helping to support and her dull-witted fitness nut of an existing boyfriend Patrick (Matthew Lewis), who is clearly fated to be dumped from his first appearance. Crucially, Lou’s family is seen as likable but hopelessly déclassé — not (or not primarily) because dad (Brendan Coyle) is unemployed or sister Trina (Jenna Coleman) is a single mother living at home with her child or because grandad (Alan Breck) is also living with them, but because mom (Samantha Spiro) is some kind of religious nut, as the authors see things.

When Will visits them, he is gracious to all (noblesse oblige!) and even says “Amen” to their grace before the meal, but the contrast between his manners and theirs is meant to inspire laughter at their expense. So, too, when Will finds out that Lou’s cultural life consists mostly in her hanging out with the family, or with Patrick, and watching TV, he tells her: “Your life is even duller than mine.” It’s all part of his conviction, which is only reinforced by his own helplessness, that she has a duty to break free of her oikish origins and live her life to the full. It is in this context that we know what to think when, after Lou’s family learns of Will’s determination to die, it is her mom, wearing a cross at her throat, into whose mouth is put the forcible and Christian case against it with her presumably outmoded view that “Some choices you don’t get to make. . . It’s no better than murder.”

But her dad, recipient of Will’s benefaction in the form of a job as maintenance man at the Castle, is more understanding: “You can’t change what people are,” he tells Lou.

“What can you do?” she asks.

“You can love them. . . and accept them for who they are.”

Ah, yes, there it is. Who they are: all the world’s and Frank Sinatra’s unanswerable claim of entitlement to doing things Their Way. I fancy that Will may even be alluding to the song when he tries gently but firmly to reject Lou’s professions of love and devotion. “I get that this could be a good life,” he tells her. “But it’s not my life.” Will by name, Will by nature, you see.

Thus, after rising above her class origins by dumping Patrick and venturing into the unknown with sub-titled movies and scuba diving in Mauritius, Lou must complete the process by leaving behind her mom’s superstitions and accepting the nouveau aristocratic culture of this “duty” (according to Will) only to oneself. And why not? There’s money in it for Lou, a chance to travel, go to university and not have a drag of a cripple or her own dependent family to look after. You’ve got to admit, it’s easier living with Will’s memory than with Will himself, and think of the fringe benefits! But isn’t this all just a form of romance novel wish-fulfilment for our hard-edged, feminist age? At least it seems so to me.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.