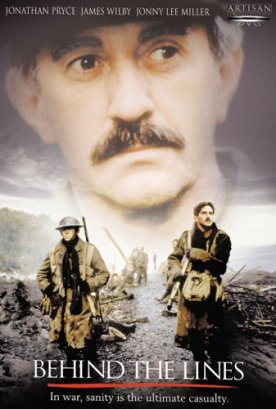

Behind the Lines (Regeneration)

Regeneration directed by Gillies Mackinnon from a screenplay by Allan Scott and based on the novel by Pat Barker is another retelling of the great left wing myth to come out of the Great War: that it was all the generals’ fault. “Half the seed of Europe,” to use Wilfred Owen’s angry poetic formulation, were sacrificed unnecessarily — or for nothing but pride and “the old lie” (to quote Owen once again) that dulce et decorum pro patria mori est. The real lie is the leftist promise that all the hard things in the world — whether fighting wars or earning a living or raising your children — can be avoided if you design a political system cleverly enough. The slaughter of the First World War was shamelessly exploited by both of the twin tyrannies, fascism and communism, that dominated the mid-century, and was vital to the success of both.

In fact, the war was a serious business. It was fought for the leadership of Europe and the world, and both Europe and the world would be vastly different places today if the Germans had won it. But the prevailing popular view of the conflict has come down to us through those that Pat Barker and her cinematic collaborators here memorialize: the overgrown, self-pitying adolescents Siegfried Sassoon (James Wilby) and Wilfred Owen (Stuart Bunce) who met at the Craiglockhart hospital for shell-shock victims (Sassoon, a war-hero, having been sent there because of a political protest against the war) decided that it was evil old men who designed the thing out of mere spite, just because they hated young and beautiful youths like themselves.

In one scene the sympathetic and understanding Dr Rivers (Jonathan Pryce), brought in to “cure” Sassoon of his heterodox political views, asks him what he hopes to accomplish by his protest, which had included hurling his Military Cross, the second highest British decoration for bravery, into the River Mersey. “What do you want?” asks an exasperated Rivers. And Sassoon — echoing one of his most famous poems — says, “I want it to stop.” To the film’s credit, the note of childish petulance is undiluted. It reminded me of nothing so much as the anger about AIDS among the homosexuals in Randy Shilts’s And the Band Played On directed against Ronald Reagan. When a huge and terrible misfortune happened to them, instead of facing it like adults, they looked around for someone to blame. And the one they blamed was the national father-figure. Hm. Wouldn’t Dr Freud find that interesting?

Interestingly, too, the supposed homosexual relationship between Sassoon and Owen which has been an object of so much academic interest is never mentioned in this film and Sassoon’s sexual orientation is only mentioned obliquely when Rivers animadverts on the army’s encouragement of comradeship and masculine love, but only when it is “the right kind of love” — as if making such distinctions were itself a sign of corruption or logical inconsistency. It also supplies an emphatically heterosexual shell-shock victim, Billy Prior (Jonny Lee Miller), as an excuse for a bit of feminine pulchritude, in the person of Tanya Allen, as well as the introduction of the alleged class-dimension of the war that the upper class Sassoon and Owen could not provide. Billy is a working class boy with nothing but contempt for the “public school fools” and “noodle brained dimwits” who, he can take it for granted, are running the war.

Even the “racist” character of the mostly unseen bad guy warmongers gets a mention when two of the doctors at Craiglockhart mention Sassoon’s Jewish blood and conclude that he has something of the delicacy of “a hybrid creature.” But Owen gets it more nearly right before he has fallen under Sassoon’s influence when he explains why it is he has not written, up until that time, poetry about the war. He once found in a trench in northern France, he tells the older poet, a clutch of skulls that could have been deposited there a year before or centuries ago, during the campaigns of the Duke of Marlborough over the same ground. Suddenly he saw in an instant, he says, the Great War as nothing but a “distillation of all the other wars” — and as such something more like a force of nature than a gratuitous political act. But in our century there will always be those who promise, and those who are foolishly ready to believe, that there is an easy way out.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.