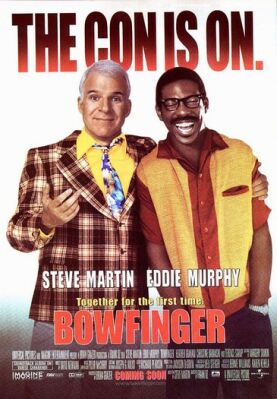

Bowfinger

Every so often a reader writes asking me to lighten up, to stop looking so closely at the movies I review and just relax and enjoy them. I always wonder why people would bother reading a critic who did that. Could they not relax and enjoy a movie themselves unless they could reassure themselves that others were doing likewise? Do they lack confidence in their own sense of enjoyment? If so, I suppose it explains their obvious sense of discomfort at the idea that someone might be seeing more in the movie than they do. But it also argues that objective and normative taste, like morality, is a natural part of our mental furniture. However much we tell ourselves that we set our own standards, either of taste or behavior, deep down inside we know we don’t, that both aesthetic and moral truth lie in shared experience.

I bring this up only because Bowfinger, directed by Frank Oz, written by Steve Martin and starring Mr. Martin and Eddie Murphy, is as near as you can get to a movie that you can “just” relax and enjoy. This is not because Mr. Martin has nothing to say beyond the string of superior jokes that constitute the film, but because what he has to say is so familiar and comfortable and, somehow, something we never get tired of hearing—namely that the creative spirit is always just a step or two away from desperation. This makes us feel better about the desperation—usually but not always more quiet than that in the movies—in our own lives and its potential for creative outcomes. In other words, it is a feel-good movie of one of the few types left—romantic comedy is still, just about, another—which still can make us feel good.

Martin plays Bobby Bowfinger, as marginal a figure as you are likely to find among the marginal characters on the fringes of the California entertainment industry. On the walls of his tumbledown bungalow, grandly labeled with a sign outside saying “Bowfinger International Pictures,” are posters advertising his career triumphs: “The Glendale Tent Players Presents: Once Upon a Mattress” with his photo in a jaunty, Robin Hood cap, for instance, or that cinematic classic, “The Yugo Story.” This is funny all right, but it raises the question why a man of such obviously modest accomplishments should now be brought to our attention as the possessor of chutzpah on a truly heroic scale? Where was this daring and nerve before, and why did it produce nothing more exciting than “The Yugo Story”?

Having read what he considers to be a brilliant screenplay by his “accountant and part-time receptionist,”Afrim (Adam Alexi-Malle) called Chubby Rain—about aliens invading the earth by hiding in raindrops—he determines to make the movie by scraping an acquaintance with Jerry Renfro (Robert Downey Jr.), a genuine Hollywood player. Amused by the obvious con-artist, Renfro tells Bowfinger that it is “a go-project”—but only if he can get Kit Ramsay (Mr Murphy), one of the biggest action heroes in Hollywood, to star. Bowfinger tries to approach Ramsay, an amusing paranoid and devotee of a weird cult called “Mind Head” which is run by Terence Stamp, but he is thrown out. Nothing daunted, he decides to make the picture anyway by filming Ramsay on the sly as his actors come up to him on the street, in restaurants and other scenes of daily life and deliver their lines. As these have to do with an alien invasion, Ramsay is terrified and responds, from Bowfinger’s point of view, with a gratifying plausibility.

In addition, he employs Ramsay’s twin brother Jiff (also played by Mr Murphy), an improbable innocent in thick glasses and braces who seems never to have left the house before. His sweetness and gullibility in the face of Bowfinger’s blandishments are the opposite of his brother’s paranoia. But most of the comedy comes from Bowfinger’s skill at using both for his own purposes—setting up a hilarious stalking scene for Kit in a parking lot in which he puts high heels on a dog or inducing Jiff to run across a busy freeway by pretending that all the cars are driven by highly trained stunt drivers. Heather Graham and Christine Baranski also add to the fun, the former by sleeping her way to the top of Bowfinger’s tumbledown operation (“Is this where I go to be a star?” she asks on getting off the bus from Ohio) and the latter by her old-fashioned theatricality (when she asks why she hasn’t got to meet her co-star, Bowfinger explains, that “We’re working in a new style. We’re working in cinéma nouveau” and she is duly impressed).

As the latest in the long line of comic American con-men that begins with the Duke and the King in Huckleberry Finn, Steve Martin’s Bowfinger is not quite the peer of, say, Professor Harold Hill of The Music Man or Max Bialystock of The Producers. We have too little sense of the humanity and vulnerability beneath the desperately slicked up exterior. But if you don’t look too deeply into things, this is about as good as it gets.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.