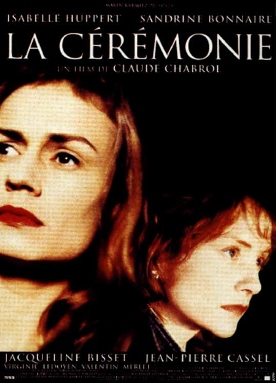

Cérémonie, La

You have to start watching right at the beginning of La Cérémonie, Claude Chabrol’s latest addition to one of the oddest and most compelling bodies of cinematic work in the world. Why does the maid, Sophie (Sandrine Bonnaire), answer the questions of her would-be employer, Catherine Lelièvre (Jacqueline Bisset) in that odd way? Why is her favorite reply, even to questions about personal preferences, “I don’t know” ? Why does she not know what day of the week it is? Why does she make a point of showing where, on her letter of reference, her former employer’s name and address are? Later, when she is shown to her room in the isolated country house in Brittany where she is to work, does she reply to the question of whether she likes it: “I don’t know” and then, “Yes, it’s fine.” Every time she is given an instruction, she replies, almost robotically, “J’ai compris”— “I have understood.”

Things begin to become a little more clear when she has a hard time figuring out where the channels are on the television in her room—and then sits zombie-like in front of it. She claims to wash dishes by hand because she doesn’t like machines, that she needs glasses when she obviously doesn’t, that she doesn’t have the right change when she obviously does. Finally, about a quarter to a third of the way through the film, its first big revelation is made. Catherine leaves her a note instructing her to press her white suit and she panics. Sophie is illiterate and is terrified of the shame of being found out.

This is where Chabrol starts to do interesting things. Obviously, this is a case for compassion, but Sophie doesn’t want our compassion any more than she does that of the rich family she works for—as would be the case, perhaps, in real life. We are never quite going to be allowed to feel sorry for her. Moreover, she strikes up a friendship with another of life’s victims. Isabelle Huppert plays Jeanne, a slatternly post office clerk who reads people’s mail, opens their packages, affects to like poetry and has a huge chip on her shoulder, especially towards all the Lelièvre family. Georges Lelièvre (Jean-Pierre Cassel), in particular, is hostile to her because he suspects her of reading his mail. Besides he knows about her past, when she was accused of killing her child but the case was dropped for lack of evidence.

Besides Georges and Catherine there is Georges’s daughter, Mélinda (Virginie Ledoyen) and Catherine’s son, Gilles (Valentin Merlet), both by previous marriages. Gilles lives at home and goes to high school, while Mélinda is a university student who comes home on some weekends, but now has a boyfriend. Her father wants her to come home on weekends more often so that they can go shooting together. We see him cleaning one of his several shotguns. Oh oh.

Sophie takes Jeanne round the house when the family is out, and she exclaims: “Ah, ça c’est la classe!”

One day, Jeanne’s battered old Citroën 2CV breaks down by the side of the road and Mélinda stops (in her nice car) to help her. She is good with cars (Jeanne claims to prefer poetry) and finds a short in the battery. There is a splendid moment when Mélinda gets it fixed and tells Jeanne to “try it now.” So loath is Jeanne to take even such an order as this from the hated and, as she thinks, spoiled rich girl that she won’t return to the car right away but turns away from it and stares off into space for a while. When Mélinda asks for a rag to wipe her hands on, Jeanne gives her a handkerchief, and when M returns it to her she throws it away.

We also discover that she has another reason for hating the Lelièvres: Catherine supposedly beat her out in a beauty contest when they were children, and then went on to fame and fortune. “She thinks I don’t recognize her, but I do.”

Mélinda has a 20th birthday party on the day when Sophie was going to spend a day with Jeanne. Catherine wants her to serve, but she sneaks off. At the party, an old gentleman quotes Nietzsche: “There are many things I find loathsome in men, but least of all the evil within them.”

Sophie meets Jeanne, who has gathered mushrooms and takes her back to her rather squalid flat to cook and eat them. Sophie tells her: “I know something about you,” and repeats the story she has heard from Georges about her having killed her baby. Jeanne denies that she killed the child. “How could a mother kill her child—even if it’s not natural.” And then she adds: “They couldn’t prove it.”

Later, Jeanne finds out something about Sophie and puts it to her in the same way. “I know something about you.” Her father was killed in a fire that was determined to be criminal arson, though she, Sophie, was never charged. “Did you kill him?” Sophie answers: “They couldn’t prove it.” Then they tumble on the bed together, laughing and tickling each other. “Enough of that. Lets go help the poor,” says Jeanne.

So they go to Secours Catholique to sort the clothes people have given in charitable donations. Jeanne is livid throughout that people obviously better off than she have given such useless junk to charity.

Georges confronts Jeanne at the post office about reading his mail. She says he can’t prove it. Then she tells him that his wife is a whore and that his first wife was too— “I’d kill myself too,” she says. She also knows something about him. Georges slaps her.

Later, with Sophie, Jeanne explains that she is sure that the art gallery that Catherine supposedly runs is a front for prostitution. It really burns her that the hated Catherine is so rich. “I’d be happy with a tenth of what they have,” she tells Sophie. With that kind of money she could realize all her dreams.

Georges finds out that Sophie has been bringing Jeanne to her room in his house and tells her that he won’t allow it anymore.

Sophie listens on an extension while Mélinda tells her boyfriend that she thinks she is pregnant and that she is terrified of her father’s finding out. Mélinda, not knowing that her secret is out, tries to make friends with Sophie. She tells her that “Dad always thinks he knows best. It’s so fascist.” She tries to persuade Sophie to join her in taking a silly magazine quiz called “Are You a Bitch?” (i.e. “salope” ). When she asks Sophie to read her the questions, she realizes that she is illiterate. Mélinda has all the right liberal reactions and is full of ideas about how she can learn to read, even offering to teach her herself, but Sophie bristles and threatens to tell her father that she, Mélinda, is pregnant. “If you talk, I’ll tell,” she says. And then, to the stunned Mélinda she adds, “I’m not the bitch; you are!”

Mélinda tells her father everything straightaway, and he decides he must fire her, without a reference, for attempted blackmail. She goes to Jeanne’s and Jeanne is sympathetic and offers to let her stay with her. Then the two of them go collecting for Secours Catholique and insult some donors about the poor quality of their charitable benefactions. So the priest has to tell them that their services are no longer needed at the church either. He tells Jeanne that she should maybe see a doctor.

The two women go back to the Lelièvres to get Sophie’s things. The family is watching Don Giovanni on TV and taping it on the boombox Mélinda got from her boyfriend for her birthday. Jeanne gets in one of her manic moods. The family do not know that she is there with Sophie, and she begins smashing photos in Georges and Catherine’s bedroom and tearing up their clothes. Then the two women begin playing around with Georges’s shotguns. Sophie has to show Jeanne how to work them—something she has learned from watching Georges. Georges comes into the kitchen and sees them clowning around with his guns. He tells them to get out or he will call the police. They shoot him. Then they shoot and kill the rest of the family. Sophie also takes a shot at the well laden bookshelves.

Sophie says she will clean everything up, and Jeanne, rather improbably, decides to go home. She takes Mélinda’s boombox. “She won’t be needing it.” Just as she is backing out of the driveway, her car breaks down again. She is in the middle of the country lane, at night, without any lights on, and she is hit from behind by a car driven by the priest and killed. That’s just a little too fraught with existentialist or fatalist or Gallic meaning maybe! As Sophie steals out of the silent house full of corpses, she sees the police taking Jeanne’s body away. One of them takes the boombox out of the back of the car and switches it on. “Do you think it’s the appropriate time?” asks another officer—and then we hear the strains of Don Giovanni and the whole scene of the murders, caught on the tape.

This is a masterpiece of cinematic narrative art. So good, in fact, that I have had to tell the whole story. So good that you almost believe in it. But you don’t, quite. Not in a psychological way. But as an example of that hard-boiled French sensibility, so congenial to the idea that the murderer lurks just beneath the surface in all of us, it is certainly a memorable cinematic experience.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.