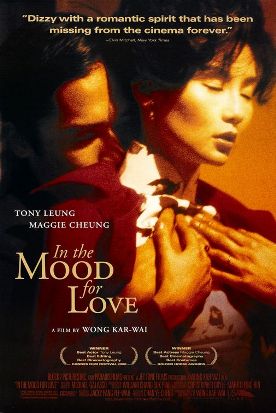

Fallen Angels

Fallen Angels by Wong Kar-Wai may be the most perfect postmodern movie

yet. Of course it comes from Hong Kong. Its characters are fragmented and

monosyllabic, its stories multiple and incomprehensible, its dialogue

minimalist, and its photography frenetic and out of focus; but boy is this hot

new movie cool. Or hip if you prefer. And that, of course, is the

point. I don’t know how he came to

think that he could be a world authority on images of cool to rank with John Woo

and Quentin Tarantino, but Wong is certainly right in thinking so. As my regular

readers will know, however, I am resolutely uncool and conscientiously unhip. In

fact, I would declare war on cool if I

didn’t harbor the dark suspicion that

that would be seen as a cool thing to do.

Cool is too powerful to take with a frontal assault anyway. Instead, we must

try stealthily to undermine it. This means getting to know its tricky ways. One

way to do that would be to go see Fallen Angels. Unfortunately, for

reasons mentioned above, I can give little guidance about what you can expect to

see. As near as I could tell, there are two stories which have little or

possibly nothing to do with each other. The first involves a moody hit man

called Ming (Leon Lai) whose main task is to walk calmly into rooms full of

people with a gun in each hand and shoot the lot of them. What kind of employer

needs to slaughter people wholesale like this we never learn. Thus the actions

we associate with a madman are portrayed as being the product of calm and

businesslike calculation. And that’s

cool.

The hit man is required by his profession, or perhaps by temperament, to have

no identity in the world. He is that perfect existential figure, a man

completely without ties to his fellow creatures. At least there is only one tie,

the beautiful young woman he describes as his

“partner”

in the business (Michele Reis). Even she does not see him face to face, but only

leaves messages about his next assignment, finds him new places to live, and

comes into the old places after he leaves in order to expunge every trace of his

having been there. In picking up the detritus of his cool but very solitary

life—soda cans, matchbooks etc—she develops a curiosity about him.

Soon we see her masturbating on the bed that Ming has recently vacated.

Masturbation is cool, as Beavis and Butthead would say.

The other story is the comic tale of He Quiw (Takeshi Kaneshiro) a young

ex-convict who was rendered dumb by a can of outdated pineapple when he was

five. The po mo joke accounts for his po mo silence, except on the soundtrack,

where He does most of the narration. He [He] lives with his aged father and prowls the streets of Hong Kong at night,

opening up businesses after their owners have gone home for the day and forcing

customers to come in and buy goods and services they

don’t want. His shampooing of a

reluctant customer in a hair salon and later selling the same man, and his whole

family, quantities of unwanted ice cream are quite funny episodes, though of

course completely gratuitous. And both funny and gratuitous are cool.

His other favorite things to do are to make endless videotapes of his father

cooking, his father pottering about the apartment, his father on the toilet, his

father sleeping. When he gets tired of this, he accompanies a girl called

Charlie or Cherry (Charlie Young) on her quest to get revenge on an

ex-boyfriend, Johnny, who has taken up with a tart called Blondie (Karen Mok).

Blondie taunts her with the news that Johnny is going to marry her. Charlie and

He go looking for her with a Molotov cocktail, but keep walking into the wrong

apartments, as Charlie doesn’t know

where Blondie lives. Instead they beat up a life-sized blonde sex doll. Beating

up is cool. So are sex dolls.

The one point of connection between the two stories comes as Blondie picks up

the hit man, who is eating a lonely burger in an otherwise deserted McDonalds,

and takes him back to her place. There she seduces him. She is a frisky and

laughing girl, and she tells Ming that she has dyed her hair blonde so that

people will remember her. It is another reminder of the assiduously-created

social isolation in which all his characters live.

“Everyone has a past, even a

killer,” says Ming’s voiceover, but he

has gone about as far as he can go to eliminate his own. He even carries a photo

of himself with a fake wife and a fake child, not only as a cover but as a

deliberate mockery of normal social connection. This is ultimately the coolest

thing of all.

Yet all this chilly blast reduces, like most things considered cool, to

adolescent posing. At the beginning and end of the film Ming tells us in

voiceover that he likes his job because he is lazy and doesn’t like to make

decisions or take responsibility.

“Who’s to live and where has been

decided by others.” A slacker hit man!

Who’d have thought it? Likewise, when He’s father dies, he says:

“I felt grown up for the first time. I

didn’t want to feel grown up. I just

wanted Dad with me.” Now he spends his

time watching his videotapes of the old boy. You’ve almost got to think that

Wong is being critical of his own material, in spite of all appearances, and

making in the end the point that the allegedly cool are in fact pathetic losers,

clinging to their adolescence. But, for some reason, I can’t quite bring myself

to think it.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.