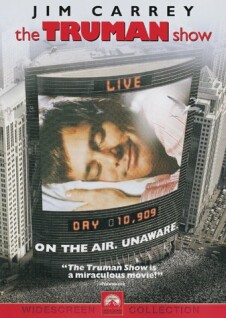

Truman Show, The

All Hollywood agrees that anytime someone makes a movie about TV or the media culture it is ipso facto a serious picture. And a picture — like, for instance, Natural Born Killers — which hasn’t a serious bone in its body can be instantly transformed into a serious picture by the addition of a “satirical” meditation on the violence- voyeurism of TV news. Thus everyone knew in advance that The Truman Show, directed by Peter Weir to a screenplay by Andrew Niccol, was going to be the high-brow movie of the summer (as the high-brow goes in Hollywood, you understand), the one that we critics were supposed to be solemn about and that the Motion Picture Academy will be expected to give awards to. In fact it is a very clever movie with no heart, like the worst of the Coen brothers, and it has no reason for existing apart from imparting a sense of their own depth to people who join in its scorn of televisual shallowness.

The idea is that Truman Burbank (Jim Carrey) is the star of something called “The Truman Show” without knowing it. The cameras have followed him all his life, from the moment of his birth, and everything that has ever happened to him has been staged by a mysterious genius called Christof (Ed Harris) — a man who runs a little empire of actors and stage hands, funded by colossal sums spent on “product placement” (in lieu of commercial breaks) on the show. When a klieg light accidentally falls through the “sky” of the perfect little town where he lives, he begins to suspect that something is not right about the artificiality of his world and the rest of the film is taken up with his attempts to verify his suspicions and to make his way to the one woman, Sylvia (Natascha McElhone) who, as an actress in the show, once tried to warn him of the truth.

Well, you’d think, looking at Peter Biziou’s garish photography which emphasizes the artificiality of everything around him, that poor Truman might have begun to get the idea by 30, the age at which he has now arrived. But he must remain unconscious of his role until now, since his awakening is meant to evoke three main themes. First, there is a deliberate dialogue with Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life, parodied in the TV man’s own favorite TV show. That was a film in which, like this one, the hero also spent the whole film trying to burst out of his small-town cocoon into the wider world only to find out that he was far more successful as a human being just by staying home. This film mocks and rejects that conclusion. The small town, called Seahaven and based on (and filmed at) Seaside, Florida, is here a horrible TV-ville, where everything is artificial and artificially protected from reality. Or “reality.” It is a place from which escape is essential.

There is also, I think, a dialogue with religious legend. Truman’s best friend, Marlon (Noah Emmerich), makes a little joke as he and Truman watch a magnificent sunset over the sea (which is really a sound stage in Hollywood): “That’s the Big Guy; quite a paintbrush he’s got!” Of course, the Big Guy in this case is Christof, the “creator” figure, whose name significantly alludes to that of the Savior. More importantly, he is shown as a kind of tyrant-God who manipulates all reality, supposedly in the name of love (all the crew of the show wear T-shirts emblazoned with the motto: “Love him; protect him”) but actually for the sake of control. He is a bully and a control-freak who believes that “Truman prefers his cell” because it is a controlled environment — something deliberately created to be “normal” as opposed to the “sick” world outside the director’s creative control.

There is some truth in the insight that his power over Truman is based on the fact that “we accept the reality of the world with which we are presented,” and he is prepared to sacrifice his creature rather than to grant him his freedom. Yet for most of us, there are very good reasons for accepting the reality of the world with which we are presented. Usually it is fatal not to accept it. That way madness lies. But sometimes a kind of mild social madness such as we have in the United States — a madness that expresses itself in TV addiction, drug or movie-induced hallucination, weird religions or wacko conspiracy theories — is simply an amusing way for us to spend some of our huge economic surplus. We can afford to be a bit crazy.

Weir’s poison appears to be the wacko conspiracy theory, since the third thematic strand lies in the film’s appeal to Hollywood paranoia. Everybody can remember the solipsistic childhood fantasy that somehow one’s self was the only certain reality, and that everyone around one, even mom and dad, even one’s best friends, might only be fakes, or in on some horrible secret that they don’t tell us. In a way this is the proto-paranoia, the model for all the sorts of paranoia that we go on to develop in adulthood. The clever thing about its use here is partly that it comes in the form of a sort-of satire (but satire in the Hollywood sense, which means that its object is flattered more than savaged) of the entertainment industry and partly that it is identified with the general Hollywood regression to childhood. When Truman tells his actress wife, Meryl (Laura Linney) that he wants to travel the world, she reminds him of their mortgage and car payments. “You’re talking like a teenager,” she says.

“Maybe I feel like a teenager!” says Truman defiantly. Adulthood itself is the ultimate plot, the ultimate trick played on us to keep us chained to the particular artificial reality where we happen to find ourselves.

All this is not to say that the film is not very clever in bringing before us the fake made to look genuine made to look fake (actually, since Seaside is a real town, it is the genuine made to look fake made to look genuine made to look fake). In a particularly memorable passage, Truman confides in Marlon, his supposed best friend since childhood, that he has this horrible suspicion that “the world revolves around me.” Marlon allays his fears with traditional anti-paranoia reassurances, and there follows one of those movie moments as Marlon assures him of his undying devotion. “If everyone were in on it,” he says, “I would have to be in on it.” And the one thing he can always be sure of is that “I would never lie to you.” All the while we see him repeating these lines from the promptings in his earpiece by Christof, who seems to write the script as the show goes along.

It’s an amusing idea, but where do you go with it? Unfortunately, where Mr Weir goes with it is to an account of Truman’s escape, ineffectually hindered by God/Christof, which ends (in a sailboat called the Santa Maria) at the literal edge of the world he has known all his life. There he finds some stairs which lead him up into the sky (again the religious iconography is to the fore), where he finds a door marked “Exit.” Opening it, he hears the voice of God, as it were, and asks: “Who are you?”

“I am the Creator” [slight pause] “of a television show that gives hope and joy and inspiration to millions.” He tells Truman that “There’s no more truth out there than in the world I created for you.” With his God-bluster, Christof insists that “You can’t leave, Truman!” But of course Truman can leave, and his leaving inspires the TV audience, estimated at upwards of a billion throughout the world, to cheer in unison, and in successive reaction shots by Mr Weir (i.e. not Christof): “He made it!” It is one of those cinematic moments just like that between the two friends in Christof’s production a short time before. In other words, Weir ends his film against fakery by celebrating his own fakery, post-modern style. But, also post-modern style, this makes it just another exercise in heartless cynicism. Truman was a real man abused by fakers—but wait! Not really. He‘s really a fake too. Ha ha. Fooled you.

The joke is wearing thin.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.