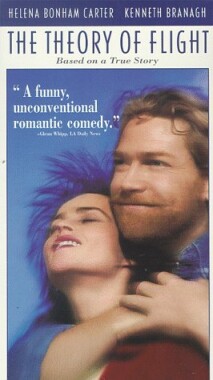

Theory of Flight, The

In The Theory of Flight, Helena Bonham Carter may have contracted

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, better known to Americans as Lou Gehrig’s

disease, but her real-life beau, Kenneth Branagh, seems to have contracted an

even worse case of Robin Williams’s disease. Both KB and RW are young men who

labor under the burden of more blessings of talent and brains than they know

what to do with and both appear to have concluded that they are going to repay

nature’s bounty by refusing to give themselves airs — indeed by spending

their lives demonstrating what nice guys they are. This they prefer to do

by making movies full of cheap uplift, in which they portray sensitive, ’90s men

driven to charming but affecting eccentricity by some secret (or not-so-secret)

sorrow. They end up bringing blessings to all around them not by anything they

are actually do so much as simply by being such nice guys — and

therefore a Healing Presence to those around them. And, indeed, themselves.

The latest exercise in this kind, directed by Paul Greengrass from a

screenplay by Richard Hawkins — for whom the story appears to be in some

degree or another autobiographical — stars Branagh as Richard Hopkins, a

failed artist who suddenly becomes obsessed with the idea of flight, or the

theory of flight, and building primitive aeroplanes. Because he causes a public

nuisance with his first attempts to fly, in London, he is given 120 hours of

community service, in the course of which he is somewhat improbably asked to

look after a young woman called Jane Hatchard (Miss Bonham Carter) who is in a

fairly advanced stage of her appalling disease and soon, alas, to die.

It’s Odd Couple time again. Richard is always off on a cloud somewhere, and

Jane is always in a foul temper, mainly because she missed her chance to be

seduced by a teen boyfriend on her 17th birthday and is, now that she is in her

twenties, thoroughly cheesed off that she is still a virgin. You can pretty much

guess the rest, though the picture is irritatingly coy both about getting us

from heart-tugging A to inevitable B and about the reasons for the delay.

Branagh seems content, like so many other actors and directors and producers and

writers these days, only to strike attitudes and not to bother himself about the

hard work of explaining why things are happening. We are never given the

slightest idea why he gave up painting, or left his pretty girlfriend Julia

(Holly Aird) who still cares about him, or why he should be insisting he is

incapable of the sexual demands that Jane is making when he obviously isn’t.

Above all, we have no clue why he should be mooning around pretending he’s a

Wright brother in the mid-1990s. Perhaps it was for no more reason than that it

makes him romantic and interesting to the chicks — which he claims is the

reason he took up painting as a teenager. “Sometimes reasons are hard to come

by,” he says, which is true enough though rather a cop-out in the circumstances.

Sometimes, too, they’re not, and we really do need at least one or two to be

getting on with. Otherwise, we are likely to think his claim to Jane that he

cannot love her not because she is “a cripple” but because he is is just

another bit of the posing and attitudinizing that this fine actor has

regrettably decided to devote his life to.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.