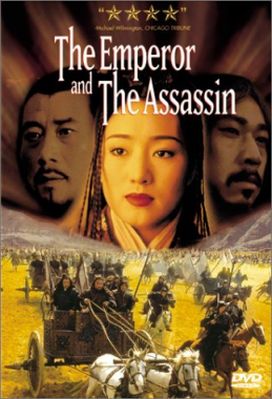

Emperor and the Assassin, The

The Emperor and the Assassin by Chen Kaige presents us with an interesting and reasonably honest look at the way power is (or at least was) wielded in the world—as perhaps only a Chinese Communist who denounced his parents to the Red Guards of Mao’s Cultural Revolution could do. True, the action takes place over two millennia ago, in the third century B.C. when the six independent kingdoms of what is now China were being united under one Emperor. True, also, that the power-game at the time involved rather more labor-intensive, face-to-face razing of cities and slaughtering of women and children than we have been used to since the invention of aerial bombardment. But the principles are if not the same exactly then close enough to offer lessons even for our American empire, the most wonderful and benevolent there has ever been.

The story concerns the alliance between Ying Zheng (Li Xuejian), king of the Qin, whose ambition it is to unify the kingdoms, and the beautiful Lady Zhao (Gong Li), his childhood playmate when he was exiled from Qin to the kingdom of Zhao. The two together have dedicated themselves to the unification of the kingdoms on the principle that it will lead to peace after 550 years of more or less constant warfare between the kingdoms. And with peace will come development and prosperity and all the things that peace and political stability does bring. Besides, the empire is inevitable, which is always the most compelling argument for empire. “Even if I die,” says the king, “someone else will complete the unification.” All this is true.

But Lady Zhao underestimates the cost of achieving this happy vision, even though she herself is prepared to pay a very high price for it. After the conquest of the Han, the next target in Ying Zheng’s plan of conquest is the Yan. But a casus belli must be found or the conquest of the Yan will provoke the remaining independent kingdoms to unite against the Qin. So Lady Zhao pretends to be on the side of the Yan so that she can persuade the Prince of the Yan (Sun Zhou) to hire an assassin to kill Ying Zheng. In order to win the trust of the Prince, she has her face branded, the mark of a convict, which is supposed to spoil her beauty—though to a modern eye the result is much less obtrusive than a tattoo. As it is assumed that no woman would do this to herself, she is accepted as another enemy of Ying Zheng’s and banished to Yan along with the prince.

There, the assassin she hires, Jing Ke (Zhang Fengyi) turns out to be a glamorous fellow with a glamorous and rather tediously elaborated back-story, just like a Hollywood assassin. It seems that, once hired by one businessman to kill another businessman and (naturally) all the second businessman’s family, he found left alive after he had killed everyone else a blind girl. The blind girl sensibly asked him to kill her too as, with all her family dead, she would have no one to look after her, social services in those days being not what they are now. Either because she is blind or because she asked, Jing Ke cannot kill her. When he refuses, she kills herself before he can stop her. Though he has not jibbed at slaughtering women and children before, he is now so stricken with remorse that he quits the assassination business and becomes a seller of sandals, the lowest of trades in the hierarchy of honor.

Well, of course, Lady Zhao falls in love with such a romantic character, and somehow manages to charm him into returning to the killing trade. You might think this would set up enough of a conflict for the movie to be getting on with, but for some reason, Chen Kaige doesn’t see it that way. He prefers to make the assassin almost irrelevant by having Ying Zheng attack and destroy Zhao, the Lady Zhao’s homeland and his own home in exile, in her absence. The particularly piquant detail of this conquest is that the defenders of Zhao, in order to make their soldiers fight harder against the invaders, round up all the children of the kingdom and threaten to kill them all if Zhao falls. Zhao falls, of course, and the kids dutifully jump from the ramparts of the city to their deaths. Why aren’t children taught to obey like that anymore?

At this stage, the Lady Zhao still clings to her Yingianism and her dreams of empire, in spite of her love for the assassin and the unhappy fate of her country. She urges her friend the king to conquer the city swiftly, before all the children die, so that he can save them from dutiful suicide. He does manage to stop the kids from jumping while there are still a few of them left alive. But while the Lady Zhao isn’t looking, he secretly slaughters the rest by having them buried alive. When she finds out about this, she becomes implacably anti-Ying and anti-empire, though a more romantic soul would have found that her love for the assassin alone would be enough to make her change sides.

To my decadent Western eye the ending is also rather a disappointment. The empire triumphs, of course. That goes without saying. The Chinese are a good deal less sentimental about these things than we are. But the assassin’s mission to kill Ying Zheng, though brought to a brief moment of confrontation, is singularly lacking in drama and scarcely even seems to involve any sacrifice on the part of the loser, any triumph or regret on the part of the winner or any passion on the part of the woman who loved them both. But perhaps I am missing something. Still, if you want a Machiavellian textbook on how to become emperor, this is your movie. It is always very watchable and mostly understandable (with the subtitles), while Ying Zheng’s way with his rebellious stepfather, his mother, his girlfriend and the independent-minded prime minister who turns out to be his father are all case studies that ought to be a part of every graduate school curriculum for Ph.D. candidates in imperial studies.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.