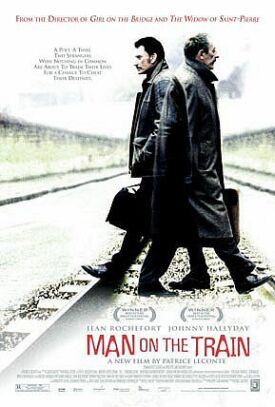

Man on the Train, The (L’Homme du Train)

The problem with L’Homme du Train (The Man on the Train), directed by Patrice Leconte (La Veuve de Saint-Pierre, La Fille Sur La Pont, Ridicule) and written by Claude Klotz (Le Mari de la Coiffeuse) is its very French notion of redemption through crime. Like last year’s Sur Mes LPvres (Read My Lips) by Jacques Audiard, it is completely in thrall to the romance of the robber — a legacy to the French cinema from Jean Genet and the post-war existentialists. In fact, the willingness to romanticize criminals has become a kind of tic of French culture, like the Hollywood notion that sexual “repression” is a fatal illness — to oneself if not to others.

Not only do both assumptions, in my view, vitiate the large portion of the cinema of their respective countries in which they intrude, but they are related by a common ancestor. This is the even more basic assumption, derived from psychotherapy if not necessarily endorsed by psychotherapists, that the sexy and violent feelings that constantly churn in the Freudian id must be indulged, respected, even encouraged in spite of the respectable world of ego and superego if a man (especially) is to be fulfilled. In this world, the only question that matters is Lady Macbeth’s:

Art thou afeard

To be the same in thine own act and valor

As thou art in desire? Wouldst thou have that

Which thou esteem’st the ornament of life,

And live a coward in thine own esteem,

Letting ‘I dare not’ wait upon ‘I would’,

Like the poor cat i’th’adage?

The moral nullity of such an attitude does not necessarily, however, lessen the acuity of the question or prevent it from being used to good purpose by great artists, as Shakespeare showed. Being somewhat less great than that, M. Leconte allows himself to get just a little too close in outlook to a certain Scottish queen, but his story of a romantic bank robber called Milan, played by the French pop singer and one-time heartthrob Johnny Hallyday, and a retired schoolmaster known only as Monsieur Manesquier (Jean Rochefort) who try on each other’s lives for size is fitfully amusing and so worth a viewing.

This is mainly because of the outstanding performance of M. Rochefort in the pivotal role of the old man, since almost everything related to the bank robbers and the bank robbery is familiar to the point of tedium. Even Sadko (Pascal Parmentier), the driver who only speaks once a day, at ten o’clock in the morning, delivering himself of some such oracular utterance as that “Revenge is misfortune’s justice” before lapsing into silence for another 24 hours, sounds like someone that Quentin Tarantino could have dreamed up. But old man Manesquier with his boyish dreams of being a cowboy or a robber even though he knows — or perhaps just because he knows — that it’s too late for him is a character to treasure and remember.

Moreover, Leconte rises above the reflexive French celebration of criminality by recognizing that the longing for another life can work both ways, and that the romantic robber himself wanted at some level to have been the schoolmaster as much as the schoolmaster wanted to be the robber. The best moment of the film comes as Manesquier’s sole pupil, a twelve-year-old boy whom he is tutoring, comes to the house while he is out and the robber, on impulse, says that he is to be the substitute for the day. The boy, who is rather dim, has been reading Balzac’s Eugenie Grandet, and Milan, who seems not to have read it himself, quizzes him about it.

“What does Eugenie Grandet do?” he asks.

“She waits,” says the boy.

“For how long?” asks Milan

“For the whole book.”

“What do you think of her?”

“She’s — patient,” says the boy, falling back on a comforting banality.

“I think she’s magnificent,” replies Milan. “People don’t have that kind of patience today.”

It is another sign of his growing admiration for Manesquier, who has also spent his life waiting. But in trying on such a life for size he realizes, as much as Manesquier does, that he cannot be the other man and must go on to the end of the course he has chosen. The robber must go to his robbery, while the schoolmaster, though eager to help, has to have a triple by-pass operation the same day. “I could call the hospital and say I was sick,” he says light-heartedly. But it’s all a dream. “Are you determined?” he asks Milan about the robbery.

“I have no choice,” says the other.

“Me neither.”

Yet the film ends on the dreamy note, which lightens its pessimism a bit at the cost of a certain sentimentality. That, too, is very French — and more charmingly so than the romantic robber.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

![Inglorious Bastards [QT, note SP]](https://jamesbowman.net/wp-content/uploads/2009/08/ingloriousbastards.jpg)