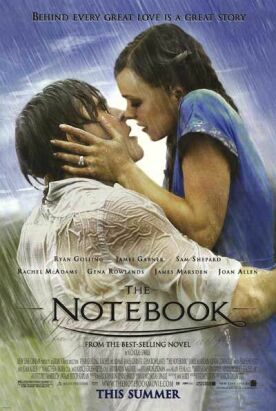

Notebook, The

Because I am such a romantic myself, I think, I intensely disliked Nick Cassavetes’s swooningly romantic adaptation of the Nicholas Sparks novel, The Notebook. Not having read the book, I can’t say whether his sickly sentimentalism has any precedent there, but the movie version of the story at any rate constantly reminds one, as sentimentalism always does, of the detachment of its emotion from anything corresponding to real life.

Part of the problem is with the corniness, from a 21st century point of view, of the story of the young lovers of 1940, played by Ryan Gosling and Rachel McAdams, separated by social class. Poor but honest Noah has the earthy genuineness of the working classes and teaches the over-protected, over-regimented rich girl, Allie, how really to live. But when they begin to get too serious, Allie’s dragon of a mother (Joan Allen) decides that such an unsuitable match must be prevented and whisks Allie away. Subsequently, mama manages to intercept every one of the 365 letters that Noah writes to Allie every day for the next year. Allie, apparently not the sharpest knife in the drawer even then, is none the wiser and thinks Noah has forgotten her. She goes to her hoity-toity rich girl’s college, works as a nurse during the war, and meets and is about to marry a wounded soldier who is in every way socially suitable when back into her life drops Noah, now himself a veteran but as much a maverick as ever, and the news that he did write and has, in fact never forgotten her even when she didn’t has a predictable effect.

Some viewers may find a certain charm in the anachronistic romance in defiance of class prejudice, a theme that was last taken seriously by movie audiences around the time that this movie is set, or a little after. But to this sentimentality is added another dollop of schmaltz in the framing story which shows an old man (James Garner) reading the story about the class-divided pair of young lovers outlined above to an old woman (Gena Rowlands). Gradually we become aware of the following facts: (1) the old woman is suffering from a form of senile dementia (2) the old man is her husband, though she doesn’t recognize him, and (3) the love story he is reading to her is their love story. There is a brief moment of recognition, but then she slips back into the fog of senility.

Instead of being touched as we should be by this, we have a sense that it is all just a bit too much. We have skipped ahead from the poor-boy-rich-girl romance, over the years of marriage, children and grandchildren, illness and heartbreak, and all the quotidian frictions of ordinary marriages, the survival of which is the true test of any romance, to the present day and the couple’s next big opportunity to put on an emotional show for us. Reality has taken a vacation for the sake of pure emotion, and the result, I’m afraid, is inspidity.We would be more prepared to let our hearts go out in sympathy to these characters if the grounds for sympathy were less obvious. But this kind of cheapness of emotional effect spoils what might otherwise have been a wholly admirable celebration of married love.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.