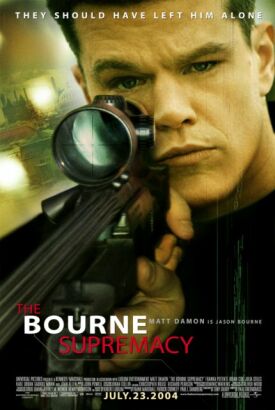

Bourne Supremacy, The

More than one writer has pointed to the coincidence of the opening of Jonathan Demme’s remake of The Manchurian Candidate during the week of the Democratic convention. And it is true that the film encodes an anti-Bush message every bit as virulent as Michael Moore’s — one that boils down to the frankly scandalous proposition that Americans have nothing to fear from Islamic terrorists compared with what they have to fear from their own leaders. As I pointed out in my review, The Manchurian Candidate is too remote from the political realities of our world — except those conjured up in the fever-fantasies of the paranoid left — to throw any helpful light on the political thinking of soberer Democrats. But there is another and better movie out now, with another star famous for his left-wing politics, which does have much to tell us of the Democratic mainstream and that side of the American national character to which it will be appealing in November.

Not that The Bourne Supremacy, directed by Paul Greengrass from a screenplay adapted from Robert Ludlum’s novel by Tony Gilroy and starring Matt Damon as the eponymous but pseudonymous Jason Bourne, is not politically tendentious. It has in common with The Manchurian Candidate a determined refusal to say anything at all directly about the geopolitical realities of the post 9/11 world. Instead of Islamic terrorism it presents us with warmed-up Cold War left-overs: a corrupt post-Soviet Russian tycoon who is hand-in-glove with a corrupt CIA agent. They conspire to frame Bourne, the poor amnesiac CIA assassin who has been on the run from the agency since The Bourne Identity (2002) for a couple of additional murders they have committed to cover their own tracks.

The corrupt US government official is of course something that the film has in common not only with Manchurian Candidate but with almost every political film to come out of Hollywood since Watergate. Isn’t it time to replace the hoary old notion of the CIA as the bad guys with a more up-to-date portrayal of the incompetents of the 9/11 Commission’s report? Moreover, even about its ostensible theme of Bourne’s identity-quest the film is itself rather amnesiac. By the time when, right at the end of the film, he finally discovers his real name and birthplace, we have all but forgotten that he didn’t know them. It certainly hasn’t seemed to matter very much since, in the earlier film, he told his girlfriend, Marie (Franka Potente) that “I don’t want to know who I am anymore. . . Everything I find out I want to forget.”

In this movie, what he doesn’t want to find out but of course does is that in his pre-amnesia days as a CIA assassin he murdered, on orders from the agency, a Russian politican — and, when she pops up unexpectedly, the politician’s wife — who was a roadblock in the way of the privatisation of Russian oil, from which the corrupt tycoon and the corrupt CIA agent made all their money. Instead of seeking his own identity, he is now seeking those who ordered the murder and then tried to frame him in covering it up. The culminating scene — after the usual quota of mostly genuinely thrilling car chases and hair-breadth ‘scapes i’ th’ imminent deadly breach — has our hero tearfully informing the 16-year-old orphan of the murdered Russian couple (Oksana Akinshina) that her mother did not kill her father and then herself, as was given out, but that both were murdered — by him.

To my ear anyway, his seeking absolution for the past he hadn’t wanted to remember from this pretty, wide-eyed child in a squalid Moscow flat resonates with the foreign policy note now being sounded by the Democrats: the note of guilt and remorse over the exercise of American power. Certainly there is nothing in the film to contradict the assumption that the clandestine activities of the CIA, and thus perhaps all attempts to project American power in the world, are morally unjustifiable. Even where fighting international evil isn’t a pretext for the corrupt self-interest of the fighters, it may be expected only to cause suffering and heartbreak to the innocent. The film could therefore be seen as being to us what the Rambo movies were to the 80’s: a kind of populist parable designed to assuage the anger and regrets of those who live intimately with a sense of America’s failures in the world.

Thus it begins with Bourne and Marie living an idyllic existence in India on the seemingly inexhaustible supply of CIA dollars he got his hands on in The Bourne Identity. Along comes a sinister Russian assassin called Kirill (Karl Urban), sent by the corrupt tycoon, and Bourne the highly-trained killing machine has to go back into action. What is the point of the tycoon’s being in cahoots with the CIA if he has to employ his own assassin? And if his purpose is to frame Bourne for another pair of murders, you would think that the last thing he would want to do would be to assassinate him. Let the poor deluded CIA case officer (Joan Allen) who still thinks he’s a renegade and a criminal take care of that. But the real point of this confusing scenario is summed up in the film’s tag-line: “They should have left him alone.”

In other words, Bourne and Marie are like irenic America before 9/11. Or Pearl Harbor. Or the Berlin Blockade. Or the invasion of Kuwait. Or any of the international crises that have from time to time dragged us back from our natural isolationism kicking and screaming onto the world stage. They should have left us alone! Like Bourne, we are recalled to action at the cost of a crippling burden of guilt — and only to find — or to think we find — at least as often as not that the real bad guys we have to take on and take out are employed by Uncle Sam. Isn’t that more or less what the Democrats, so voluble on the subject of George Bush and Dick Cheney and so largely mum on the subject of Islamic terrorism, really have to say to us in this election year? And the success of The Bourne Supremacy suggests that this part of their message, at least, may have some resonance with the already war-weary American people.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.