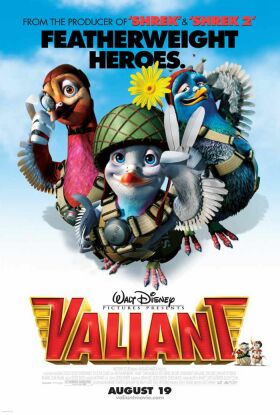

Valiant

The high-brow history of our literary, artistic and cinematic avant gardes tends to obscure the fact that today’s equivalent is led by children. What is “post-modernism” if not a childish kicking over — we disguise the petulance and childish resentment at mature achievement by calling it “deconstruction” — of the carefully-constructed artistic and cinematic edifices of the past? No critic or literary theorist has more successfully deconstructed the heroic myths of the past than the Disney team has in their movie versions of them. But from Hercules to Aladdin to Pocahontas Disney has tended to play it safe by picking for its po mo versions myths that are a long way in the past and mostly unfamiliar to today’s children. For brighter children and adults cajoled into taking their kids to these movies, they work on another level as a sort of inside joke.

Now, with Gary Chapman’s Valiant, a British team of animators and actors has given the Disney treatment, or the equivalent, to a more recent myth. It is a myth that we all, especially the British, take — or used to take — much more seriously, namely that of Britain’s heroic resistance to Hitler and the Nazis. Except that Hitler and the Nazis don’t appear in this film. Neither do the British. Their machines, especially war machines, and buildings appear from time to time, and at one point a voice that presumably belongs to Sir Winston Churchill is heard. But otherwise the Second World War, on this showing, is a war of animals. Mainly birds.

The heroic birds are pigeons of the Royal Homing Pigeon Service, a real entity which is said to have made real contributions to the real war effort. But here, amid the unreality we have come to expect from the movies, it is run by the pigeons themselves, who enthusiastically conform to recognizable human types. As, of course, do the bad birds, who are falcons in the service of the Nazis — and in Nazi-gothic uniforms that you would think might be rather an encumbrance to a falcon. Naturally, these creatures are given to the “Ve haff vays of making you squawk” school of movie villainy.

That line, by the way, actually occurs, uttered by the most evil of the Nazi birds, Von Talon (voice of Tim Curry) to a terrified British pigeon called Mercury (voice of John Cleese). It can hardly be said to count as news that a falcon should have ways of making a pigeon squawk, but the surprise, the moment of po mo frisson, comes when the exquisite tortures that poor Mercury has in store turn out to be neither human nor animal but yet more Disney drollery: an old Victrola recording of Tyrolean yodeling. And when that doesn’t work there is a “truth serum,” administered in a suggestive if not actually obscene fashion, that is meant to produce equally hilarious results as Mercury abandons his “stiff upper beak” and announces his intention of talking about his “feelings.” It may be a war, that is, but no one actually gets killed, or even badly hurt in it. Or if they do, it’s no one we know. People, maybe, who otherwise don’t figure in this war. Even the bad guys may get a good spanking, but so far as we know survive their encounter with British justice.

Disney would also clearly approve that the greatest heroes are the littlest pigeon of all, a wood-pigeon called Valiant (voice of Ewan McGregor) who is desperate to “do his bit” with the homing pigeons, and his side-kick, a raffish bag of filth called Bugsy (voice of Ricky Gervais) that he finds hanging out, as pigeons tend to do, in Trafalgar Square. The relationship between Valiant and Bugsy conforms to the Disney pattern between hero and sidekick — and that of DreamWorks’ Shrek movies, which were also produced by Valiant’s producer, John Williams. That is, the hero is youthful or physically robust, and brave, naïve or idealistic while the sidekick is older, unashamedly wimpy, very talkative and knowledgeable in the ways of the world.

The pattern is also carried out in the way that the movie is, even more than it is visual caricature, a platform for gags translating human situations and language, at least those that will be familiar to the children from the movies, into what are easily imaginable as being predicated of animals. Thus the pigeon drill sergeant (voice of Jim Broadbent) says to his pigeon-recruits: “I will make birds of you turkeys if it kills you.” And what about that rollicking pigeon-equivalent of Allons-y, “Let’s make wind!” Obviously stereotypes are the life-blood of such a movie. The French Resistance, led by a sexy mouse called Charles De Girl (Sharon Horgan), can’t let the brave Brit air-pigeons go without a chorus, again on the Victrola, of Edith Piaf belting out “Non, je ne regrette rien,” while the wicked Von Talon hums along in the shower to — see if you can guess — “The Ride of the Valkyries.”

Such details tell us where we are, namely in cartoon land. That, as we have all now learned, is the place where even a war in which many of the kiddies’ grandparents might have taken part is made safe and non-threatening to them, heroism and villainy alike are rendered comical and virtually without cost, and there is an uplifting moral to take away such as “It’s not a bloke’s wingspan that counts; it’s the size of his spirit.” True enough, I suppose, but if I were a kid I don’t know that I’d be inclined to believe it if everything around it were charmingly fake.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.