Crockumentaries

From The American SpectatorWhich came first, the impoverishment of America’s political discourse or Hollywood’s inability to think politically in anything more complicated than the crudest sort of slogans? It’s a chicken-and-egg problem whose further discussion is pointless, but it suggests a connection between the two things that should not be lost sight of when we emerge, blinking, into the light after seeing yet another so-called documentary designed to outrage us with its Manichean view of the world. They seem to me to be coming along at an ever-increasing clip, these Michael Moore-inspired crockumentaries, and the style of them has become so, well, stylized by now that it is readily adaptable to any subject from terrorism and the war in Iraq — still the documentary world’s favorite subjects — to McDonald’s hamburgers. What they all have in common is what they also have in common with an ever-increasing proportion of the larger political debate, not only in America but in the Western world, namely the assumption that the political opponents whose views they caricature are either knaves or fools — and frequently both.

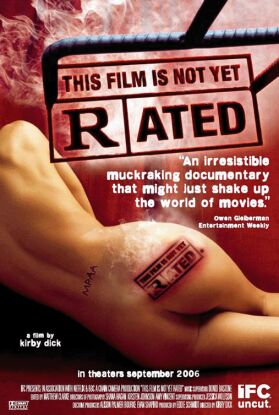

Take Kirby Dick’s movie This Film Is Not Yet Rated, which attacks what it sees as the “censorship” of the Motion Picture Association’s Ratings Board — that is, the hitherto anonymous folks who decide whether movies are classed G, PG, PG-13, R or NC-17. I say “hitherto” anonymous because it is Mr Dick’s idea of a merry jape to hire a lesbian private investigator to track these people down in order to name and shame them, as if their being hidden away from the public gaze were itself evidence of wrong-doing. This effort provides the film with a narrative thread on which he then hangs a number of talking head interviews. These are of two types: those which are designed to embarrass defenders of the ratings system and make them look ridiculous and those which express, with varying degrees of vehemence, the film’s own point of view of the system — which, like the preacher’s view of sin, boils down to the fact that it’s agin’ it. Some may notice a certain irony in Mr Dick’s opposition to “censorship” and what one of his talking heads calls “brainwashing” in view of his own ruthless censorship of the other side, or the reduction of it to nothing but a bit of PR fluff.

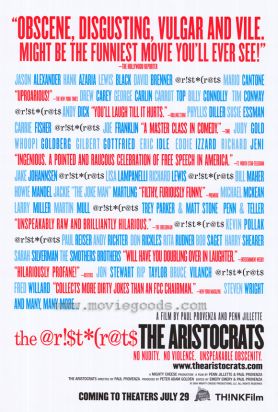

For a flavor of the film’s rhetorical jejuneness, consider some of the following statements. By showing graphic cinematic sex, says one interviewee, “I’m not teaching this broad” — referring to a typical 16 year old girl — “anything she doesn’t know.” Yeah, that’s what the defenders of the ratings think: that without these pictures in the movies they watch, kids would never know anything about sex or even their own bodies. Likewise, Maria Bello, a glimpse of whose pubic hair in The Cooler, very nearly doomed that movie to an NC-17 rating, says that, in contrast to uptight Americans who have “desexualized sex. . . because we are so afraid of it,” sophisticated Europeans think that sex is “just a part of life; just a part of nature.” Another palpable hit there, my fellow blue-noses, for do we not stoutly maintain that sex is not a part of life (is it part of death, perhaps? kinky!) and not a part of nature? Mary Harron, director of American Psycho, talks scornfully of “the fear that sex will dissolve the social bonds” — as if we didn’t see sex dissolving social bonds every day. Finally, Becky, the Lesbian P.I. says of her awakening to the joys of lesbianism: “How could something that makes me feel so good be wrong?”

Gosh, what a concept! For all those centuries past, moral philsophers have agonized about right and wrong when all they needed to remember was that, if it feels good, it’s right! Guess they won’t make that mistake again. All such vacuous remarks are just variations on the film’s one and only idea, which is that the attempt to protect children from sexual images is irrational, wicked and oppressive — in short, as Mr Bingham Ray of October Films puts it to Mr Dick’s camera, “fascist.” Well, guilty of every other sort of rhetorical carelessness, why should the picture stop at that one? One reason I resist using the term “Islamo-fascism,” increasingly popular among those who otherwise share my views of it, to describe the currently most exigent threat to America’s security is that virtually every other use of “the F-word” — as Mr Ray ironically puts it — is of this type: that is, absurdly hyperbolical. It’s got to the point now where any time I hear the word, alone or compounded and not used in a narrowly historical context, I immediately assume that the speaker can have nothing serious to say. About anything. For although there are many more parallels between the political philosophy of Benito Mussolini and that of Osama bin Laden than there are between Mussolini and Jack Valenti, the use of the latter comparison and others like it have spoiled “fascism” for any serious analogical purposes.

Just look at Aaron Russo’s America: From Freedom to Fascism, which is even more sloppy and promiscuous about its use, charging that, because of a smorgasbord of nefarious conspiracies by those in power, “Americanism is now like Naziism, Communism, Fascism.” Yet when I reviewed Mr Russo’s paranoid rant negatively on the Spectator’s website, I got hate mail from those who would defend him for, I must suppose, the sole and sufficient reason that his inclusion of the income tax and the Federal reserve system among his dark conspiracies is a congenial idea to some conservatives. It’s yet another example of rhetorical impoverishment that for so many the only question to be asked or answered about a putative political argument is whether or not it advocates one’s own point of view or that of one’s political enemies. Even a much better film, like Kevin Knoblock’s Border War, which actually includes a sympathetic and articulate opponent of its own views about illegal immigration, doesn’t allow him to make more than a personal case and offers no spokesmen for the the more abstract political and economic arguments in favor of some form of legalization.

Of course, the reasons are not far to seek. In the movies, emotion sells and reason is a bore. Thus the anti-war, anti-military documentarian Patricia Foulkrod, writes in her “Director’s Statement” that “I produced and directed The Ground Truth because I felt it was time to stop hiding behind the politics.” Hiding behind politics? But politics is what the war is about! This is like saying that she wanted to describe a football game without hiding behind the rules or the scoring — but just to show a bunch of guys running around and hitting each other with no reference at all to why they are doing it. Even if she thinks they shouldn’t be doing it, she can have nothing useful to say about it if she doesn’t at least explain what they think they’re doing. But in today’s documentaries, it’s always open to you to assume that they don’t think about it at all but are mindless nincompoops — like the Marine who tells her camera that what attracted him to the Corps is that “They’re mean, they’re tough, they’ve got cool uniforms and chicks dig ‘em.” So when the recruitment officer had brought out the list of occupational specialities, he had said: “I want to be a grunt; I want to blow s*** up.”

That is the kind of comment you want to take with a grain of salt, at least if you have any more discernment than a documentary film-maker. Like the converted sinner who needs to exaggerate his former sinfulness in order to stress the wonder of his conversion, Miss Foulkrod’s collection of antiwar Iraq veterans have to stress their former stupidity or naïveté, as they now see it, in order to impress us with the wisdom of their newly enlightened state. And dutifully, one after another, her subjects tell us that nobody told them, before they went to war, how awful it would be. Why, people are badly wounded and even die in wars! Who knew? “There’s no surgeon general’s warning,” says another of these morally, physically or psychologically traumatized vets. “They don’t tell you the consequences.” The naïveté of such remarks is far greater than that of the guy who wanted to blow s*** up. As if anyone could tell you the consequences; as if it were possible, by telling them, to avoid them!

If you say war, you also say wounds and death and maiming and psychological anguish a-plenty, often that of civilians and others who did nothing to choose it as well as to the soldiers who did choose it, however innocently. The only serious question then becomes when, if ever, do you choose war? Needless to say, that is the very question that The Ground Truth never for a single moment considers. One former soldier says of his friends who died, “I told myself that they died for a reason, but I couldn’t find that reason; I couldn’t justify it to myself.” One sympathizes, of course. There must be others who feel the same way. But, equally, there must also be some who could find the reason, and it’s just a little bit difficult to believe that Miss Foulkrod made any very exhaustive efforts to find them. Why should she when she knows that the movie-going public, like the political culture, no longer expects anything more cogent or intellectually engaging than the most arrant propaganda?

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.