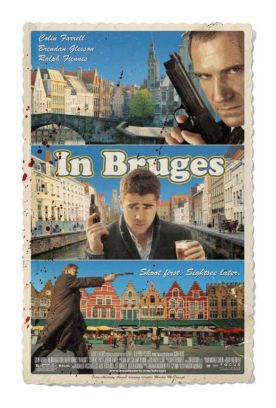

In Bruges

I think it was Quentin Tarantino who first used the word “medieval” — in Pulp Fiction as part of a threat by boss Marsellus (Ving Rhames) to a couple of hapless rednecks that “I’m-a get medieval on your ass” — to mean scary-violent. Up until then, “medieval” in the vernacular, if it meant anything at all, had meant “extremely old-fashioned.” Suddenly, now that even mainstream movies were going in for graphic gore-fests in a big way, it meant “extremely new-fashioned.” I think there was even more to the paradox than this, actually, since the sort of hideous tortures and executions that Mr Tarantino doubtless had in mind when he had Marsellus mention pliers and a blow-torch had been practised by the official culture of the middle ages against heretics and traitors. Yet Mr Tarantino was instantly recognizable as the voice of the unofficial culture — which now seemed to be welcoming both traitors and heretics as well as the methods once favored for dealing with them. It was all rather confusing until you realized that neither the torture nor the invocation of the Moyen Age was meant to be taken seriously.

This may be nothing more than an interesting tidbit from our bizarre cultural history of the last 40 years but it is worth reflecting on in connection with Martin McDonagh’s In Bruges, which seeks to squeeze a little more juice out of the same idea that the representation of murder without compunction (if not necessarily torture) was a way of bringing things medieval back into fashion. Ken (Brendan Gleeson) and Ray (Colin Farrell) play a couple of Irish hit-men who hole up in Bruges, “the most well-preserved medieval town in the whole of Belgium,” on orders from their boss, Harry (Ralph Fiennes), back in London. There is presumably meant to be some kind of thematic interpenetration between the killers’ business and most of their conversation and the cultural heritage all around them.

Mr McDonagh’s film also follows Mr Tarantino’s lead in presenting the hired killers, as a comic cross-talk act — an up-dated and edgier version of Abbott and Costello. A lot of the film’s humor depends on Ray’s dislike of the cultural riches among which he and Ken find themselves and Ken’s attempts to talk him into an appreciation of them. “If I grew up on a farm and was retarded, Bruges might impress me, but I didn’t and it doesn’t,” says Ray. At a key moment, he wonders: “Maybe that’s what hell is: eternity spent in f***ing Bruges.” Ray only begins to perk up when he comes across a movie set using, like this movie, Bruges as a backdrop. He runs excitedly to tell Ken: “They’re filming midgets!” On the film set he meets a pretty drug dealer (Clémence Poésy) and her would be thug of a boyfriend (Jérémie Renier) as well as the American midget (Jordan Prentice) and more rollicking comedy ensues.

Gradually, however, it emerges that the two men are hiding out in Bruges because Ray has inadvertently killed a child back in London while carrying out a hit on a priest. The child had been waiting to confess his sins. Harry has sent them to Bruges as an odd gesture of humanity. It is a place that he himself loves, and he imagines that he is giving his two employees a big treat. It never occurs to Harry that Ray, an aggressive philistine, might not share his enthusiasm for the place. And Ken wishes to protect him from the knowledge of Ray’s ingratitude. For in Ray’s case, it is to be a last treat before he dies. Harry has decided that he must pay with his own life for the life of the child. “You can’t kill a kid and expect to get away with it,” says Harry. “You can’t. You just can’t.”

This makes Harry, ruthlessly evil as he is, the only person in the movie who actually believes in something. He has “principles,” he tells us, and principles, like torture, seem to fit naturally in with the medieval context so handsomely provided by Bruges. He tells Ken if he had done what Ray did, he would have put the muzzle of his pistol in his mouth on the spot and pulled the trigger. But the film is a bit vague about what, besides not killing any kids himself and not allowing anyone else to get away with kid-killing, Harry’s principles might consist of. They are, however, similar to those of other movie criminals and perhaps even — who knows? — some real criminals, in having to do with honor. When Harry tells his wife that he has to go to Bruges on business, she asks him if it’s going to be dangerous. “Of course it’s going to be dangerous. It’s a matter of honor!”

Ken, whom we have learned to trust, confirms Harry’s sense of honor, and cites it as the reason, when it looks as if Harry is going to kill him too, why he refuses to fight back. It all may begin to suggest that “medieval,” as applied to the art and architecture of the Belgian city, also stands for a way of looking at the world characteristic of such modern-day equivalents of Renaissance princelings or Italian dukes as Harry or Marsellus and utterly at odds with the decencies common to hit men and other ordinary folks. But mainly the movie is just a vehicle for Mr McDonagh’s witty dialogue and a display, as so many movies these days are, of its maker’s way with comically exaggerated villainy and his sophistication in knowing that the “honor” in the mouth of the villain is only what makes him comic.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.