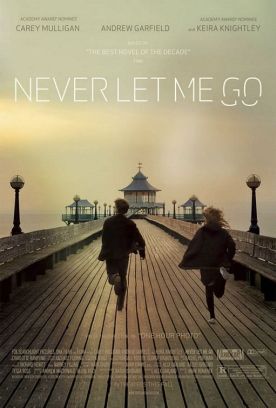

Never Let Me Go

What I liked best about Mark Romanek’s adaptation of Kazuo Ishiguro’s novel Never Let Me Go is also what I liked best about the book, which took what could so easily have been just another s-f or “dystopian” fantasy and put it instead into the real world. Admittedly, it is not our real world but a sort of weird, alternative reality that is constantly pushing at the edges of our residual mimetic expectations by its resemblances to our own. Its world is unmistakably England, but an England which, for some reason presumably connected with the fictional scientific advance that is both the novel’s and the movie’s central premiss, took a different sociological and cultural turning half a century or more ago and is now both disturbingly and fascinatingly unlike itself. In fact, this feature of the movie is even more striking than it is in the novel, perhaps because of the visual echoes, lushly and evocatively photographed by Adam Kimmel, of familiar things which, I think, makes this one of those rare movie adaptations that manages to improve on its original.

One reason is the movie’s semi-documentary quality. This is an England in which the sexual and cultural revolutions of the 1960s appear never to have happened but which instead managed to preserve a slightly rancid version of the public-spiritedness and willingness to sacrifice that were characteristic during the period of the postwar socialist government of Clement Attlee — along with a class structure more rigid even than the pre-war one. People who thought that post-war “austerity” was the price that had to be paid for progress have continued to dominate, culturally and politically, and so arrived at a similar consensus about medical progress. Everyone seems to accept that the nobility of the alliance between medicine and social thought to wipe out disease is so unquestioned as to justify even the existence of an underclass of clones, seen by non-clones as only half-human. Even the clones themselves, kept in semi-segregation from the rest of society, seem to agree — at least until they are 30 or so and it is time for them to “complete” the process of donating their organs to their overlords.

In the novel, the word “clone” doesn’t appear until about two thirds of the way through; in the movie it never appears. This is just one of the ways in which we are denied the easy satisfactions of utopian fantasy and the cheap sense of superiority that comes with it. That a clone has no word for clone seems no more remarkable than that a fish, if it could talk, might have no word for water. It is taken for granted. The three clones at the center of the drama, Kathy (Carey Mulligan), Ruth (Keira Knightley) and Tommy (Andrew Garfield), are among the most privileged of the clones, however, having been sent to Hailsham, a typical British boarding school of the 1950s to be taught useful skills, and even some limited acquaintance with humane studies such as art and literature, until they are old enough to have their organs “harvested” for the benefit of the fully human characters who remain only shadowy presences both in their lives and in our observation of them.

The three are involved in a love triangle that appears at first to have nothing to do with the social and political implications of their lives as ambulatory bags of spare parts for others. At age 12 or so, shy Kathy (Isobel Meikle-Small) is drawn to Tommy (Charlie Rowe) who is a new boy at Hailsham and is being picked on by others. But her bolder and more sexually advanced friend Ruth (Ella Purnell) comes between them and steals Tommy away. The relationship between Ruth and Tommy somehow survives until they have grown up and become Miss Knightley and Mr Garfield, respectively, and they become sexually active, though they both remain close friends with Miss Mulligan’s Kathy. Years later, when Kathy becomes a “carer” — that is, a clone suffered to live a little longer than others in order to help them through their various “donations” — she again meets Ruth, now on the verge of “completing”, who wants to make it up to her for stealing Tommy away. “You two had real love and I didn’t, and I didn’t want to be the one left alone,” she confesses.

On one level, we inevitably wonder about the conscience of a clone, but on another the question of who loved whom seems to them of the utmost importance because of a rumor among the clones that if two of them could prove to the authorities that they were truly in love, they could be granted a “deferral” to live a few more years of their lives together before meeting their clone-fate. Whether this rumor is true or not is the only real point of dramatic tension in the movie, so it would be unfair of me to give it away, but Cathy’s and Tommy’s quest for a deferral is eventually what leads them and us to an inevitable confrontation with the moral vacuity at its center. The surprise for us, though obviously not for them, is how much their world looks like ours after all. The exercise in alternative history has been for a reason. It’s not to show us the dreadful fate that awaits us in an apocalyptic future; it’s to remind us that that future is here and now.

And maybe it always has been. Imagine, for example, a world like the one God made — if you will permit the hypothesis for the sake of argument — composed, as it is, of the fortunate and healthy on the one hand who have rich, long and fulfilling lives, and those who are doomed to pain and early death on the other. But this world differs from God’s in being man-made, deliberately designed by human intelligence to keep separate the sheep from the goats. Obviously, it would be intolerable. And yet we live in such a world and do not, cannot consider it so. Kathy’s concluding reflection about Tommy, that “I was lucky to have had any time with him at all,” becomes the prelude to her wondering if their lives have really been so very different from the lives of normal people who, when they come to the end of them may also feel as she does: “We haven’t had enough time.”

Finally, the movie can’t quite escape it’s presumptive s-f and propagandistic origins. Insofar as it can be and even must be read as a political statement about denying full humanity to some for the benefit of others, it concludes with the unchallengeable banality that we must not allow the state to treat people like this — a reassuring “message” that allows us to go home with a sense of our own righteousness and immunity from any implication in the human tragedy we have witnessed. Yet at the same time, like the best utopian fiction, like 1984 and Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure, for example, we also come away from it with the uneasy sense that, like the clones, we are already living the nightmare ourselves and just don’t know it yet. It is an ancient commonplace that death makes us all equal, but the pop-cultural eternity on offer in Never Let Me Go suggests the long vistas of perspective the saying gives us on our lives which may never be fully explored.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.