Young Adult

Once when I remonstrated with a young man of my acquaintance about his laziness and want of industry, he replied: “But being lazy is who I am!” We live in the age of “who I am,” sometimes varied as “the real me.” The popularity of the conceit may owe something to the political awakening of homosexuals, who have been historically used to keeping quiet about their sexual orientation. As part of the process of nerving themselves to go public about it (or “come out of the closet”), the idea of “who I am” or “the real me” has been immensely useful to them. But the purpose of the conceit is in its essence no different than it was for my lazy young friend. That is, it is designed for self-justification. That by which one chooses to identify oneself cannot be, on this thinking, wrong or mistaken or something to be reformed or ameliorated. If it is essential to their very existence, to who they are, then that existential truth must be accepted by anyone not intending, like some tyrant or cruel oppressor, to deny or negate that existence.

Also influential in the propagation of the ideology of “the real me” was the children’s album, book and TV special titled “Free to be you and me,” produced by Marlo Thomas and the Ms. Foundation for Women back in the seventies, which taught a whole generation of American children at the early identity-forming stages progressive ideas about what was — and, crucially, what was not — culturally approvable versions of who they were. Thus when football hero Roosevelt Grier sang of how “It’s All Right to Cry,” he was also subliminally teaching that it was not all right not to cry, or to suppress one’s tears, as little boys had been taught to do for generations, in the interest of “being a man.” The suppression of one “stereotype” involved the creation of another, politically correct one.

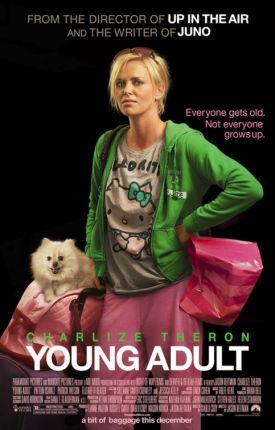

One of the songs from this album, “When We Grow Up,” sung by Diana Ross, is played over the closing credits of Young Adult, and its refrain, “We don’t have to change at all,” is a neat summing up of the movie’s message. I’m not too fond even of movie messages with which I agree, but I wouldn’t have minded this one if I had thought that the film-makers — screenwriter Diablo Cody and director Jason Reitman — had been capable of appreciating the irony of “We don’t have to change at all” and seen that this supposed freedom not to change means being imprisoned in the self. Not only do we not have to change at all, we have not to change at all. There are hints, here and there in the movie, of the self-awareness demonstrated by Ms Cody and Mr Reitman in their earlier collaboration, Juno of 2007, but the sinister ideology of “Free to be you and me” is too strong for them in the end. The selfish, nasty, unattractive qualities of their heroine, Mavis Gary (Charlize Theron), are treated as her ready-made destiny, as impossible to be changed or tampered with as her much more pleasing appearance.

Indeed, much less so. Mavis, a thirty-something divorcée who ghost-writes romantic fiction intended for young adults, is very good at making herself look even more attractive than nature has already made her. Feeling vaguely dissatisfied with her life and hearing that her high-school boyfriend, Buddy Slade (Patrick Wilson), has recently become a father, she decides to return to her home town of Mercury, Minnesota, to take him away from his wife and family. Her putting on her war-paint for this struggle with a less-attractive rival (Elizabeth Reaser) is a recurrent motif in the film and suggests just one of the ways in which outward beauty betokens an inward ugliness, part of which consists in the inability (or unwillingness) to change.

This self-imprisonment she shares, as we eventually discover, in crucial ways with Mercury and with her fellow Mercury Injuns, now re-named the Indians for reasons of political correctness. The first person she meets on her return is a pudgy, nerdy high-school classmate named Matt (Patton Oswalt) who used to have the locker next to hers but whom she only remembers as “the hate crime guy.” Matt, it seems, had been badly beaten and, in fact, permanently crippled by some jocks from Mavis’s more popular set who had thought, mistakenly, that he was gay. “When they found out I wasn’t really gay, then it wasn’t a hate crime anymore,” he says ruefully. It’s a clever line but one that smells a bit of the lamp, as they used to say. We can more easily imagine Ms Cody writing it than we can some real-life version of Matt saying it.

At first, Young Adult seems to be a fresh and original take on a classic sort of American movie in which a big city sophisticate returns to her small town roots to discover a more authentic and fulfilling mode of life, as in Sweet Home Alabama. Matt plays the role of chorus and gives voice to the sense of decency and social responsibility that used to characterize small-town America in Hollywood’s lens and that we still expect to act as at least something of a corrective to Mavis’s cynicism and predatory wickedness. But gradually we realize that Matt is as much a prisoner of his self and his past and of the bitterness both have created in him as she is, if not more so. His is a stunted growth that ends up only reinforcing the movie’s basic idea that people don’t really change very much and probably shouldn’t even try to change.

Since character development is thus taken off the table, the movie turns instead to a satire on the absurdities of young adult fiction and the romantic fantasy world that it encourages young people to live in. Romance itself is seen as little more than a discreditable dodge, a cover for naked self interest, to which even this otherwise cynical purveyor of the stuff may be susceptible. Thus Mavis says to Matt, who naturally looks askance at her determination to win Buddy away from his wife and child, “Don’t you get it? Love conquers all. Haven’t you seen The Graduate?” We’re in a different Hollywood tradition than we expected, it seems. And, throughout, we hear voiceover of Mavis composing her latest (and, it seems, last) romance in the series and are invited to draw the obvious parallel between her story and that of her glamorous but, alas, fictional alter ego, Kendall Strickland.

Kendall is a girl whom Mavis describes as having “a gracious, effortless beauty that glowed from within.” Glowing from within is of course the opposite of what Mavis’s beauty does — a point underlined for us by juxtaposing the voiceover description of Kendall with Mavis’s dolling herself up for her date with the long lost Buddy — a rather hapless stand-in for Ryan, the boy from Waverley Prep that Kendall Strickland is in love with. But the final turn to “Free to Be You and Me” can only suggest that the film-makers are unable to think of anything else to say about this desperately sad woman whose beauty, instead of glowing, pales and sickens from within than a Stuart Smalley-like, “That’s OK.” I would like to see in this and the concluding song an ironic critique of the “who I am” culture, but I just don’t think that, with all her talents, Ms Cody was up to that. She, herself, I fear, inhabits the same dark prison of self that her heroine does.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.