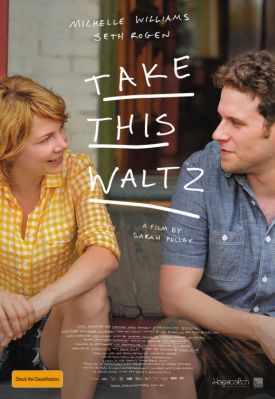

Take This Waltz

As an actress, the young Canadian Sarah Polley is always interesting, always watchable — for example, in The Sweet Hereafter or Go (1999) — and the same was true of her as the director of her first feature, Away From Her (2006), in which she got a magnificent performance out of Julie Christie as an Alzheimer’s patient who forgets she’s married. In her new film, Take This Waltz, another fine actress, Michelle Williams, proves worthy of Miss Christie’s example as Margot, a much younger wife who also forgets she’s married, but without the excuse of clinically certifiable dementia. Her amour fou for Daniel (Luke Kirby), the rickshaw-pulling hippie artist across the Toronto street from her comes across, nevertheless, as a not dissimilar form of mental disturbance — though perhaps it is only a temporary one. At least the movie allows us to think of it in that way without quite medicalizing her passion as a form of the currently-fashionable malady of “sex-addiction.”

As a result, Miss Polley, who also wrote the screenplay, at least keeps the moral mess in which adultery involves people at the center of attention. She even pulls back from the clinical realm, to some extent, other, more firmly established sorts of addiction. Margot’s sister-in-law, Geraldine (Sarah Silverman), in particular, is a recovering alcoholic who delivers the film’s key line: “Life has a gap in it. It just does. You don’t try to fill it like a lunatic.” You know at once that this is hard-won wisdom from someone who has experienced and profited by the therapeutic approach to moral problems from the inside. In the words of the late Mitch Hedberg, who expired from his own addiction to heroin at age 37, alcoholism is a disease, but it’s a disease people can get mad at you for having.

The point is that even the hint or the tease of a pathological explanation for Margot’s behavior suggests something trivial and faintly comic about her grand passion, making her look more like a stage-drunk (at which Miss Silverman also has a turn) than the coolly deliberate Stéphane Audran in Chabrol’s La Femme Infid le (1969), a film with which this one might otherwise have borne comparison. Instead, it is more like Adrian Lyne’s woeful remake of Chabrol, Unfaithful of 2002, which insists on the divine madness of which it sees all its characters as being in the grip to such an extent that the movie itself appears to suffer from a similar compulsion. Sarah Polley has more subtlety and better actors at her command in Miss Williams and Miss Silverman, who shows that she is more than just a comedienne. Unfortunately, one can’t quite say the same of Seth Rogen as the cuckolded husband Lou, who writes cookbooks with only recipes for chicken in them and whose charming sad-sack doesn’t rise to the sort of moral seriousness essayed by his conscience-stricken wife.

As we see it today, the half-moral, half-pathological nature of self-destructive behavior poses a problem for contemporary artists, but potentially also an opportunity, since it allows them to go back and forth between the two ways of looking at the same thing, just as light can be seen as both particle and wave. I don’t think that Take This Waltz succeeds in taking that opportunity. What it does do, mainly thanks to Miss Williams, is to give us a portrait of a woman caught where she says she most hates to be, “in between things.” Everyone who has ever experienced an inappropriate sexual attraction will recognize Margot’s vacillation between physical desire and moral repulsion, and by far the best part of the film shows her unable to move either in one direction or the other. Sooner or later, we know she will have to choose, and once she does things go rapidly downhill from there into banality and cliché from which Geraldine’s unexpected moral aperçu provides only a partial rescue.

Weirdly, Margot and Lou engage in an ironic sort of love-talk which threatens to put things back in the psycho-pathological realm. “I love you so much I want to grind your spleen in a meat-grinder, a rusty one,” he says to her, or “I love you so much I want to inject your face with a combination of swine flu and the Ebola virus.” And this is apparently a custom which long antedates any thoughts of infidelity on her part. What is that about? Perhaps it is a compensation, of sorts, for Lou’s passivity and studied moral indifference later on when he asks her, “How can you be sorry for doing what you had to do?” As this is the prelude to a post-affair reprise of their unfunny running gag from the days of their intimacy — “I just bought a new melon baller, and I want to gouge your eyes out with it” — we may think that at least now that latent hostility has a rationale to it.

The movie begins with a historical re-enactment at an 18th century French fort in Louisbourg, Nova Scotia, which Margot is visiting in connection with her job writing tourist brochures. A little period sketch is put on for the tourists in which a malefactor is dragged forth by a costumed bailiff or constable, who invites the gawping spectators to observe. “Everyone gather in the square for the public humiliation,” he cries. An embarrassed Margot is called on to administer the mock punishment with a whip and is admonished to flog the prisoner harder. Subsequently, Margot finds that she feels much more the sense of (public) shame than that of (private) guilt as a result of her illicit passion. The real public humiliation turns out to be hers. But it is still only a feeling and produces no apparent dramatic consequence. Like the Leonard Cohen song that ends the movie and gives it its title — like the movie itself — this idea seems to be striving toward profundity without knowing how to achieve it.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.