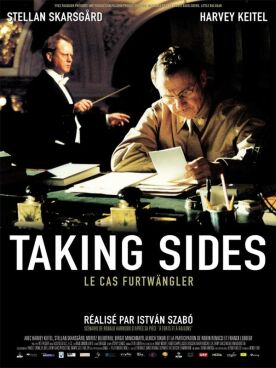

Zero Dark Thirty

Judging by the reactions to it that I have read, the question about Zero Dark Thirty isn’t so much whether it must be discussed or evaluated in terms of its scenes of CIA-conducted torture but whether it can be discussed or evaluated in any other. When Naomi Wolf can compare it to Triumph of the Will and its director, Kathryn Bigelow (The Hurt Locker), to Leni Riefenstahl, then you know that the possibilities for civilized discussion are already at evaporation point. Yet, whatever you think of the torture scenes, you should recognize that that comparison is wide of the mark, even apart from its shameful rhetorical excess. For Leni Riefenstahl was a propagandist, someone with an ideological parti pris which she sought to impose upon her material. In the case of Zero Dark Thirty, it is Miss Wolf and her fellow opponents of torture who are the ideologues and Miss Bigelow who is defying ideology for the sake of art.

A reasoned moral opposition to torture, that is, must begin from the premiss that it is wrong even if it “works” — that is, even if it produces the possibly life-saving or otherwise vital information for whose sake it is administered in the first place. There is nothing inconsistent with this point of view in Zero Dark Thirty. Although you would have to say that it appears to come down on the side of those who justify torture by its results, its central character, a woman called Maya (Jessica Chastain), is not seen as an unambiguous hero. Her obsession with finding and killing Osama bin Laden turns her into a lonely and somewhat repellent figure whom it would be easy to see as someone who has given up too much of her own life in order to take what she sees as a personal revenge on the late terrorist mastermind. Miss Bigelow allows a note of American triumphalism to creep in at the end, presumably for the sake of the box office, but the overall moral picture is more balanced and recognizably life-like.

Those who, like Naomi Wolf, state categorically that “torture does not work” are the ideologues and propagandists here. What they mean is that in their version of reality — and an ideology is first and foremost a proprietary version of reality — torture cannot be allowed to be seen as working. They may cite, as she does, “five decades of research” purporting to prove that torture never works, but we know instinctively that the “research,” also ideologically motivated, had to have been designed to prove that and only that. Common sense tells us that, however poor a tool torture may be for acquiring information in the real real world, unrigged by ideological presuppositions, it must sometimes work. Say it worked in the case of the hunt for Osama bin Laden, as some people, not obviously liars or torturers themselves, claim it did. Only then does the central moral question of whether it was worth it arise. The ideologue’s version of the story does not allow for any such subtle moral reasoning but can only reduce the question to a cartoonish contrast between good victims and evil torturers, which is typical of propaganda.

All that having been said, however, I wonder if Kathryn Bigelow, working from a script by Mark Boal who also partnered her on The Hurt Locker, can quite escape responsibility for sending discussion of the central question for America’s foreign and defense policy in our time down this moral blind alley. However helpful or not helpful torture may have been in showing us the way to Abbottabad, it could hardly have been as central to the process as its disproportionate share of attention in the movie would suggest. By stressing the torture as much as she does, she not only inflames opinion among left-wing ideologues but also obscures the more important questions — at least from the military and diplomatic point of view — raised by what used to be called “the War on Terror.”

The main such question is this: What are we fighting for and how much are we prepared to sacrifice to win? By reducing things to a personal grudge-match between Maya — heartbreaking recordings of telephone conversations from people in the Twin Towers on 9/11 which begin the film supply her motivation — and the now-deceased jihadist, the film not only adds to the latter’s exaggerated sense of self-importance but also shows little or no interest in these more pertinent matters. At one point, a character in the film quotes from a letter written by Osama bin Laden: “Continue the jihad. The war will go on for a hundred years.” So far, you’d have to say it looks as if he was right — about the duration of the war if about nothing else. But Zero Dark Thirty’s obsessive focus on him, matching Maya’s own, makes the movie into a reflection of what appears to be the Obama administration’s view, namely that, once we killed Osama, the war was virtually over.

There are some good things about the movie’s portrayal of America’s intelligence-gathering operation. For one thing, it shows — one imagines accurately — a CIA spooked, as it were, by the fiasco over the non-existent Weapons of Mass Destruction in Iraq. In one particularly memorable scene Maya confronts a room full of her CIA colleagues as they weigh the probability of its being Osama who is holed up in the Abbottabad compound. The consensus is for sixty per cent. Then Maya speaks up. “One hundred per cent,” she says, like the winning bidder at a high stakes auction. There is a stunned silence around the table until she adds: “OK, ninety-five. Because I know certainty freaks you guys out. But it’s one hundred.” Clearly, we are meant to remember this when, as the Navy Seals are preparing for the raid, one of them says to a more doubtful other that he believes Maya’s story about their objective. “What part convinced you?” asks the doubtful one.

“Her confidence,” he replies.

“That’s the kind of concrete data point I’m looking for,” says the other. “I’ll tell you buddy, if her confidence is the one thing that’s keeping me from getting ass-raped in a Pakistani prison I’m gonna be honest with you, bro’, I’m cool with it.”

|

That kind of black humor also has the ring of reality about it, as does the hint of disdain, otherwise almost entirely if improbably absent from the movie, for someone of Maya’s sex who takes on some of the authority of leadership in such a quintessentially masculine military operation. But then the feminist ideology, which would forbid any notice of such a thing in an otherwise sympathetic character, must have been even harder for Miss Bigelow to resist than that of the anti-war left. The only other time I can remember when the question of “gender” is raised, Maya is surprised that her new CIA station chief in Pakistan gives her no argument when she makes demands on him for help with her project. “I have learned from my predecessor that life is better when I don’t disagree with you,” he says, as if she were a nagging wife. One cannot imagine such a line being directed to another man, but the director is presumably quietly on board with Mark Boal in presenting Maya’s quest as, at least in part, an example of girl-power.

The final half hour of this more than two-and-a-half hour movie is taken up with a more-or-less straightforward account of the raid on the Abbottabad compound, and it is much the best thing about the movie, managing to be taut and suspenseful throughout even though everybody in the audience will already know how it all comes out. Having Miss Chastain pacing nervously as she waits for news from the men who alone can finish the job to which she has devoted her whole life not only belies, to some extent, her earlier arrogant certainty, but also helps to raise the emotional energy by putting us, along with the whole country, in her watchful, waiting place. Moreover, it hints of that wider social context in which she stands for the values and virtues of liberal democracy — including, in spite of the torture, the value it places on human life — in its confrontation with a fanaticism to which such morally troubling questions as are raised by Zero Dark Thirty do not occur.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.