The Dream Team

From The New CriterionAs she waded ashore through the surf at Key West on Labor Day, the 64-year-old endurance swimmer Diana Nyad said to a crowd of bystanders and waiting reporters who had gathered there: “I have three messages. One is we should never, ever give up. Two is you never are too old to chase your dreams. Three is it looks like a solitary sport, but it’s a team.” Well, it certainly is a team — 35 members strong, according to The New York Times, not counting the one who actually did the swimming part. But what kind of “sport” is it? They used to say that baseball was America’s national pastime, but nowadays I wonder if we don’t have to give the nod to “dream” chasing. And the dream, ex hypothesi, is always the drearily familiar one of celebrity. In the case of Miss Nyad, who comes by her apparent nominal determinism (though the Greek Naiads were exclusively fresh water spirits) through her Greek stepfather, it was endorsed by the President too, who “tweeted” his congratulations to her along with the redundant exhortation: “Never give up on your dreams.”

For her, we can be pretty sure, the dream was not just being the first to swim, on her fifth attempt, the 110 miles from Havana to Florida’s southernmost extremity in two days and nights without the benefit of a shark cage but the fame of having done so. Or rather, a further increase in the fame that her earlier attempts on the Florida Straits, along with a number of other “firsts” in long distance swimming, had already won for her. After her fourth unsuccessful attempt, she was extensively profiled in The New York Times Magazine, posing stripped down to show the marks of the jellyfish stings that had stopped her, with the sort of attention that would once have been vouchsafed to explorers or mountaineers — among whom, by the way, there were numbered very few attractive women. Yet her achievement in itself didn’t quite capture the imagination like being the first to reach the South Pole or to walk on the moon. One could not quite see her replying to the question of why she kept trying to swim from Cuba to Florida as George Mallory explained his multiple attempts on Mt. Everest: “Because it’s there.” Without those waiting reporters, without regular bulletins on TV or radio news programs on her progress along the way or that write-up in The New York Times, her “dream” would have had little power to inspire others — or even, one suspects, herself.

|

Of course none of the media people who were her collaborators in celebrity-manufacture acknowledged their role as members of her “team” — any more than they do when antiwar or other “demonstrators” turn out to make a spectacle of themselves on behalf of publicity for some political cause. We know that they wouldn’t be there without the media’s presence to amplify their voices in the marketplace of ideas, but it’s not quite playing the game to say so, or to question the intrinsic worth of the stunt or the idea thus made famous. Expressing their own moral indignation in order to shame the powerful is, after all, their dream, and the media are nothing if not believers in dreams. All media is advertising, but those who are shrewd enough to peddle a product that the media can use to promote themselves or their favored causes are able to get it for free. This is never more true than for the dreams of celebrity that only the gods of the media can make come true.

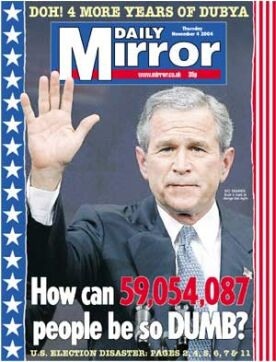

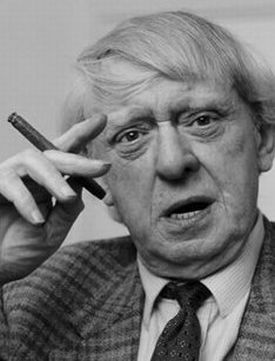

The day before Ms Nyad emerged like Venus from the sea-foam, Sir David Frost dropped dead of a suspected heart attack — also at sea, as it happens, on a cruise ship where he had been traveling as a highly paid lecturer. A bona fide genius in the creation of celebrity, including his own, Frost once owned the television rights to The Guinness Book of World Records, a volume full of the pointless achievements of lesser Diana Nyads, all made for the sake of an even more minor and fleeting form of celebrity than hers — often, indeed, almost Warholian in its brevity. Frost was there for them, however, these little people of the celebrity culture, as he was for Richard Nixon to whom in 1977 he offered an early version of the media’s redemption in the form of a series of celebrity interviews in the course of which he managed to wring from the (inevitably) “disgraced former president” a sort of apology to the American people for the scandal that went under the name of Watergate.

Nixon is now, of course, the very paradigm of the abuser of power brought low by the media (in their own telling of the story anyway) who exposed the discreditable truths he would have hidden. But he subsequently became an object of fascination — a kind of celebrity by default, since he had made celebrities of so many others. Frost was not the least of these. He was of course already a celeb when he came to interview Nixon, but each man had the effect of burnishing the celebrity credentials of the other. In Britain, Frost was a more or less constant television presence for half a century, but he might have been forgotten in America without the Nixon interviews — a pivotal point in his life, as in that of the media. For in a way Nixon’s story was also their story; the story of his fall from power was also the story of their rise to it. You might almost say that they owed him a measure of the celebrity that, because of him, politicians would henceforth seek as their consolation for wielding ever less genuine power.

Frost’s career, too, was paradigmatic. The lead of his obituary in the London Daily Telegraph read as follows: “Sir David Frost, who has died aged 74, began his career in television satirising the patrician Establishment and ended it with a knighthood, a duke as a father-in-law and a reputation as the television personality politicians on both sides of the Atlantic most wanted to be interviewed by.” Something similar could be said of the media themselves during his lifetime, who went from being courtiers of the great to being their greatest detractors and back again to being courtiers as they themselves were given entrée into and subsequently transformed the Establishment — which is what they used to call the ruling class back in the days fifty years ago when it was being ruthlessly pilloried on That Was the Week that Was, the BBC television show that made Frost famous.

Partly as a result of that collapse of ancient habits of deference and respect, the British were convulsed ten years later by the question, put to the electorate by Prime Minister Edward Heath in 1974, of “Who governs Britain?” The people decided by a slim margin that the answer was not Mr Heath and his Tories. Rather, it was (provisionally) the United Mineworkers, the Trades Union Congress and the Labour Party, which then existed mainly to do the unions’ bidding. Americans never got to vote on the question of who governed them, but it was decided in the same year, and the media and the judges who, between them, took down Nixon have been their de facto governors ever since. The election of President Obama has only disturbed that consensus to the extent that people forget he, like most politicians today, is a creature of the media — someone who, in the absence of even so much of an achievement as Diana Nyad has to her credit, owes everything to them.

One reason Watergate is so central an episode both in the media version of America’s history and in the life of David Frost is that it ended not with the resignation of the President in August of 1974 but with the Frost interviews three years later, which have since been (like the rest of the scandal) memorialized and mythologized on stage and screen. Peter Morgan’s Frost/Nixon made a hero of Frost just as All the President’s Men made heroes of Woodward and Bernstein. In doing so it made the point that the role of the now-triumphant media in our political process was and remains not just one of disciplining the nominal holders of political power but also one of “humanizing” them, which is the word they use to describe the process of celebrification — begun, in Nixon’s case, by Frost and posthumously completed by Mr Morgan’s play. The process of becoming a celebrity is also that of being broken to the media’s yoke. The celebrity must know that he is now their creature, their beast of burden, and will have to live henceforth to do their bidding, though their yoke is easy and their burden is light.

I’ve never been a big fan of the comic stylings of Comedy Central’s Jon Stewart, but he once did a hilarious parody of this humanizing process called “Adolf Hitler: the Larry King Interview” “Larry, look,” said the late German dictator. “I was a bad guy! No question! I hate that Hitler!” Now, he says, with the help of therapy he’s a new Hitler. “You know when you stop having to control everything, it’s very freeing!” Dan Rather once attempted something similar with Saddam Hussein (see “Rather Not” in The New Criterion of April, 2003) on the eve of President George W. Bush’s march into Iraq, presumably because humanizing mass murder seemed at the time like a useful tactic against the war. As I write, Charlie Rose has taken his microphone to Damascus to interview Bashar al-Assad. The latter is reported to have spoken movingly of his relationship with his late father and predecessor in Syrian dictatorship and the fact that he, Bashar, didn’t gas anybody, despite what the world may think.

While President Assad looked to the celebrity culture for redemption, President Obama must have seen it as a jailer, forcing him into the incoherence of deploring the TV pictures of dead children, killed by Assad’s poison gas, while simultaneously tacitly acknowledging the pointlessness of any conceivable response on our part. Like a poor actor reading his stage directions along with his lines, he even took care to make clear his desire to strike at Syria in such a way as to cause no serious or lasting harm to the putatively evil dictator or to do anything to advance the cause of his enemies, whom we are now meant to recognize as being nearly as evil as he is. What, then, does he mean to accomplish by unleashing, Bill Clinton style, a bit of remote death and destruction that will not be too deadly or destructive? Why, to “send a message” of course. Alas, it is not a message about what the civilized world can allow a rogue dictator to get away with. Not any more. No, it’s only a message about America’s moral disapproval of gassing children. We can let the other 100,000 or so people killed in the civil war slide, but we’re bound to issue some impotent protest about that. Maybe on one of the out-takes of Charlie Rose’s interview we can see Mr Assad slapping his forehead and crying: “Who knew?”

It’s another case of what Greg Weiner calls “narcissistic polity disorder” — the sort of thing that is merely comic when it appears in, say, Anna Wintour’s statement of a year or so ago, dissociating herself from a flattering but pre-civil war interview her magazine had run with the dictator’s wife. “Subsequent to our interview, as the terrible events of the past year and a half unfolded in Syria, it became clear that its priorities and values were completely at odds with those of Vogue,” she wrote. You don’t know whether to laugh or cry, however, when the President or some member of his administration announces, in much the same vein, that whatever intervention is being considered at the time “is not about who occupies this office at any given time.” Still less, apparently, is it “about” Mr Assad or his evil deeds. No. “It’s about who we are as a country.” The words are Mr Obama’s in his Rose Garden speech on the day David Frost died. They echoed his words of explanation two years previously for intervening in a belated and half-hearted way in the Libyan civil war — with what results we saw last year in Benghazi — that not to have done so “would have been a betrayal of who we are.”

Secretary of State John Kerry also struck the Anna Wintour note, perhaps by way of apology for the intimate dinner he and his wife enjoyed with Mr and Mrs Assad in 2009, when he said that the proposed strike into Syria “is also about who we are — we are the United States of America, we are the country that has tried, not always successfully. . . to honor a set of universal values.” Even when we don’t act, it’s OK to do a little bragging about “who we are,” as Mr Obama showed on the most recent occasion when he reiterated his long unfulfilled promise to close down the prison at Guantanamo Bay: “The idea that we would still maintain forever a group of individuals who have not been tried, that is contrary to who we are.” And yet he continues to “maintain” them there, forced to do so (as he now claims) by Congress.

Poor man! Like President Assad, President Obama understands that the celebrity culture seeks out opportunities for empathy like a pig hunting truffles. Accordingly, it judges people not on their deeds but their words, and on the creditable feelings those words, elicited by an infinitely empathetic interlocutor, invariably express. “I hate that Hitler,” says Jon Stewart’s contrite Fuhrer to Larry King about his formerly genocidal self. It’s the authentic plea of those practised in the art of self-justification by appeal to some inward, passive but “true” self, distinct from the one who has done something wrong. “Who we are” is thus ostensibly the morally purest and highest principled of nations, proud of our attempt, not always successful, to live by “a set of universal values.” But “who we are” in reality is the country whose self-proclaimed moral superiority has become permanently paralyzing because of the very need to keep proclaiming it, as if to an imaginary talk-show host — one to whose effort at “humanizing” what Richard Nixon, pre-Frost, foresaw as the world’s “pitiful, helpless giant” everybody in the world is now tuned in.

Those who argued, including many whose views on foreign and defense policy I respect, that American “credibility” was at stake in the Syrian intervention were not wrong, but I think they underestimated the extent to which American credibility had already been fatally undermined in the region and around the world, mainly by the efforts of the last decade’s anti-war movement whose self-righteous preening not only helped get Mr Obama elected but also set the tone for and put limits on the scope for action of the Obama presidency. This he owes in no small part to his adoption of the media’s view that any use of military power beyond the merely symbolic is no longer an option for any leader wishing to avoid the Bush treatment. It hardly seems possible that he himself takes any other view. But at least we may be confident that, however disastrous that presidency may be for those our media moralists now pride themselves on leaving to their own devices, he will never give up on his dreams.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.