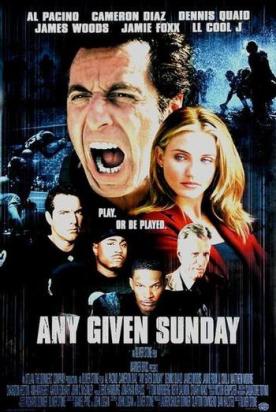

Any Given Sunday

Oliver Stone’s latest, Any Given Sunday, is not for those, like me, who are put off by the Oliver Stone’s style of moviemaking. Leaving aside for the moment the fact that what he has to say is often historically inaccurate, irresponsibly speculative or politically tendentious, the worst thing about a Stone movie is the attempt to stir up excitement by having people talking at the same time, and loud rock or rap music playing over their voices so you can’t hear them anyway. His camera is constantly moving, and the quick cutting style appropriate to someone who really ought to be tested for Attention Deficit Disorder is only punctuated by maudlin scenes of drunkenness, debauchery or self-pity masquerading as deep thoughts about life, the universe and everything. As if this were not bad enough, he goads on Hollywood’s hammiest actors—in this case, Al Pacino, into overacting even more egregiously than they would do in any case.

Yet without these stylistic tics, Any Given Sunday might have been a football movie straight out of the 1930s or 1940s. For underneath its aggressively contemporary exterior, it tells the classic story of an ill-regarded third-string rookie quarterback, Willie “Steamin’” Beamen (Jamie Fox), who is called on to step in for an injured veteran, Jack Rooney (Dennis Quaid). He has some initial successes which promptly go to his head, suffers some reverses and soon, under the patient tutelage of the wise old coach, Tony D’Amato (Mr Pacino), learns what it takes to be a leader of men (either on the football field or on the battlefield) as well as a mensch to his friends and teammates and to his pregnant girlfriend, Vanessa (Lela Rochon).

The frenetic and off-putting style seems to me to be Stone’s way of apologizing for offering up what he presumably thinks of as cornball stuff like this. Something similar happens in David Maraniss’s recent biography of Vince Lombardi called When Pride Still Mattered. Maraniss says that he uses that title, like Richard Ford from whom he takes it, with “a certain irony,” but he does so in order to forestall the criticism that he is engaging in mere nostalgia and uncritical admiration for Lombardi, whose presence also looms in Any Given Sunday from its epigraph to the photo on the coach’s wall. As a result, Maraniss’s book is marred by a constant tension between what it is really telling us—which is that Lombardi was, indeed, admirable—and a lot of fashionable academic and journalistic chaff designed to disguise the fact.

Stone also apologizes for his hidden hymn to classic masculine values by kowtowing (I take it) to Hollywood feminism by casting a young and beautiful woman as the wicked football-club owner, Christina Pagniacci (Cameron Diaz). She behaves without honor to the players and coach who risk life and limb for victory, and Charlton Heston, in a cameo role as the league commissioner, swears that she would “eat her young.” This I guess is meant to reassure fashionable opinion of a bizarre kind of even-handedness: if Stone’s women are not allowed to possess masculine virtues, at least they may possess masculine vices. In the same way, the much-injured Jack Rooney’s wife, Cindy, greets the news that he wants to retire by slapping him and screaming: “You’re a football player! You have two or three more years in you. I will not listen to this b***s***.”

This is not exactly the only false note struck by this curious picture. The one I treasure most is when Pacino’s coach begins his inspirational locker-room speech to the team before the big game by saying: “I’ve made every mistake a middle-aged man could make….I chased off anyone who ever loved me…” Oh dear! The therapeutic, confessional culture rears its ugly head even in the middle of this testosterone-soaked moment. That’s not a surprise. The surprise is that, if you can overlook such nonsense and the shrillness, both aural and visual, with which it is presented, Oliver Stone has produced a very old-fashioned movie which tells a truth about men in conflict and struggle that the elite culture wants to hide from us. Never has his conspiracy-sniffing faculty been put to better use.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.