Here on Earth

Maybe Ali McGraw couldn’t have managed it, but one would have liked to see

the beautiful and talented Leelee Sobieski given a chance to move an audience

without having to die. Alas, it was not to be. Here On Earth, written by

Michael Seitzman and directed by Mark Piznarski, is a remake of Love

Story for teens. For how quaint now seems the relative innocence of the

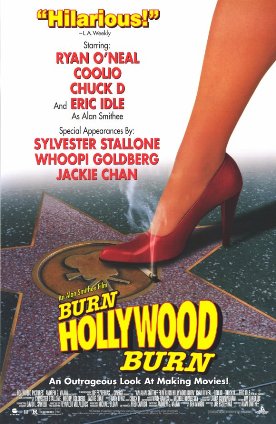

20-somethings played by Miss McGraw and Ryan O’Neal thirty years ago. Now 18

year-olds Kelley (Chris Klein) and Sam (Miss Sobieski) are obviously sexually

experienced already when they assume that a mutual attraction will lead

straight to intercourse—do not pass romance, do not collect $200.

Presumably Messrs Seitzman and Piznarski think that the situation will

provide all the romance this “hook-up” requires. Kelley is a snotty and arrogant

rich kid at a private school in Massachusetts called Ralston. Out joy-riding

with some pals in his graduation present, a new Mercedes, he insults a couple of

townies, including Sam’s boyfriend, Jasper (Josh Hartnett), who challenge him to

a drag race. In the ensuing accident no one is hurt, but one of the cars crashes

into an improbably old-fashioned and rickety gas-station-cum-diner (called

Mabel’s Table) belonging to Sam’s parents which subsequently burns down. What

mom always says (says Sam)—“As long as we’re all alive, it’s nothing more than

a bad day, right?”—has a certain poignancy in the light of subsequent

events.

Kelley and Jasper are both sentenced by a wise and tough local magistrate

(like all wise-and-tough judges in the movies she is a black woman) to work

together with Jasper’s father (Michael Rooker) to rebuild the diner. “It’s a

chance to put back what you took,” says the judge, “and “maybe not just build a

restaurant” but along with it some “character.” To add to the human interest,

Kelley must board with Jasper’s family for the summer. On the one hand, Kelley’s

snobbery and arrogance—at first he won’t even eat with the family—have to be

broken down; on the other hand, Jasper too has to learn to overcome some of his

hostility. His mom asks him: “Did you ever think you’re the lucky one? I didn’t

see a mother in that courtroom.”

How perceptive of her! Turns out that Kelley’s mom, to whom he was devoted,

committed suicide—as, indeed, who would not who was married to his nasty,

overbearing, rich-guy dad—and he, Kelley, found the body. It is his secret

sorrow that, once discovered, makes Sam love him. But before that, Sam is

physically attracted to him. First things first. Like the man in the Coke

commercial, Kelley appears to her bare chested on the construction site. “I’m

hot,” says Sam. “I think I’ll get something to drink.”

This, I think, is what is supposed to pass for witty dialogue. Here’s some

more. When Sam has got her drink, she engages Kelley in conversation. He

confesses that he has killed Jasper’s little sister’s pet mouse.

“You could get arrested for that,” Sam playfully opines.

“Will there be handcuffs?”

“Do you want handcuffs?” says saucy Sam.

“Depends who’s putting them on.”

Even more ludicrous than these clunky lines is the scene in a meadow where

Sam’s willing seduction is consummated and Kelley compares her body parts to the

states of the Eastern seaboard as he fondles them one by one. When he gets to

Massachusetts, she murmurs dreamily, “Massachusetts welcomes you.”

There is one sort-of funny line in the movie. When caught in bed in

the paternal mansion in Boston by Dad and Dad’s girlfriend, an awkward breakfast

ensues between the two women while Dad is sternly telling Kelley to ditch the

girl and concentrate on Princeton and success. “So how did you and Kelley meet?”

asks Dad’s girlfriend.

“He burned down my family’s restaurant,” says Sam.

But it is not enough to save this movie from the general bad writing and the

clichéd, dying-girl situation which, transplanted to the teenage years

and embellished with some coy sex and a lot of maudlin “poetic” ambiance seems a

trifle sick.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.