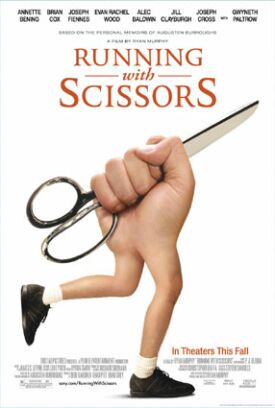

Running with Scissors

As between last week’s monster-mom — Laura Linney’s religious hypocrite in Driving Lessons — and this week’s — Annette Bening’s self-absorbed poet and Anne Sexton wannabe in the movie version of Augusten Burroughs’s best-selling memoir, Running With Scissors — I much prefer this week’s for sheer awfulness. The trouble is that, as the movie-Augusten (Joseph Cross) tells us in his voiceover narration right at the outset, she’s just a bit too awful. “Nobody’s going to believe me anyway,” he says. This is not quite true, but it does point us to the paradox that Miss Bening’s Deirdre would have been more believable if she had been fictional. Presented to us as the real Augusten’s real mother in Ryan Murphy’s cinematic adaptation of the book, she taxes credulity in a way that she would not have done if she had been made up. Belief does not quite stagger and fall beneath the burden it is forced to carry, but we nearly always feel it sweating and straining to hold up.

That it does hold up as well as it does is mainly a tribute to Miss Bening’s terrific, Oscar-worthy performance. Not only does she manage to make her own character look real but that steadily- maintained reality at the center of the film is almost enough to prevent its story of craziness in the house of horrors where Augusten is forced to spend much of his childhood from spinning out of control. Almost, but not quite. The house belongs to Dr Finch (Brian Cox), the psychiatrist and guru to whom Deirdre surrenders not only her son but her will, her critical faculties and such common sense as she might once have possessed. The doctor is the kind of guy who, if he were fictional, would be criticized not just as a bit too awful to believe but as an utter caricature. Augusten Burroughs has thus laid down a challenge: disbelieve him if you dare, but Dr Finch actually existed. Truth, they say, is stranger than fiction.

As a movie-goer I rather resent such challenges, but as a skeptic with regard to the therapeutic culture, I confess to having enjoyed Dr Finch and his whole lunatic household enormously. Besides the doctor there is his zombie-like wife Agnes (Jill Clayburgh) who watches vampire movies on TV while munching canine kibble; his dutiful daughter Hope (Gwyneth Paltrow) whom we first encounter lying on the couch in her father’s “masturbatorium” beneath framed photos of the Queen of England and Golda Meir; his rebellious daughter Natalie (Evan Rachel Wood) to whom Augusten plays patient when she gets out dad’s electro-shock therapy machine and, last but not least, his homicidal, gay adoptive son, Neil Bookman (Joseph Fiennes).

All of these actors act up to the example set by Annette Bening, but the cumulative effect of so much dysfunction concentrated in one place is to split the film in two — rather in the way that the young Augusten must have seen his life split in two. On the one hand there is his mother’s dream-world of poetic distinction, and on the other there is this phantasmagorical circus of pathologies that might have been designed to distract him from the pain of his mother’s absence. It certainly distracts us. In one way, at least, the doctor and his household have been fictionalized, for what must have been for the real-life Augusten unspeakably dreadful about living in that house has become laugh-out-loud funny in the movie — though we may feel guilty about our laughter.

Not that mother is not funny as well. What can you do but laugh at someone who only takes time out from writing the poetic masterpiece that will finally get her, she thinks, on the Merv Griffin Show to decoupage her rejection letters? “I want a daily reminder of my artistic journey when I become famous,” she remarks. “It will keep me humble.” But we can no more detach ourselves from her than Augusten can. Dr Finch, that is, is a malignant buffoon, but the boy whose childhood he did so much to blight can now treat him as nothing more than a specimen presented for our examination. The best revenge, perhaps, comes from the grown-up Augusten’s having no more emotional stake, either of love or hate, in the memory of his absurd ménage. But it’s obviously a different story with his mother. And it shows. Her casual and unrepentant destruction of her child’s home and family — not to mention that of her husband (Alec Baldwin) — in pursuit of a delusional poetic glory was and is unforgivable.

That inert but deadly moral datum sits like an inoperable tumor at the heart of the fun that the mature Augusten has made of his young life, and so we find the smile dying on our lips. Artistically this is a shame, because it means that the funny-serious movie never quite joins up with the funny-funny one. We have two points of view, one of the damaged Augusten and the other of the detached Augusten. Both, to be sure, give us some splendid satire: of the narcissistic gospel of self-fulfilment and self-revelation, of feminism, of psychotherapy and of that which they all share, the 1960s models of confessional poetry and political and personal “liberation.” But the emotional doubleness corresponding to this artistic dualism leaves us unsure about why we should care. Is this meant to be only Augusten’s not-completely sad story or is it something more than that? Is it, for instance, also a bullet to the heart of our soulless, self-seeking culture? It might well have been that, but neither Augusten Burroughs nor Ryan Murphy seems to have wanted to pull the trigger.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.